And now, a question that makes Christian historians uneasy. Is it possible to identify how God works through history?

My guess is that many ordinary Christians would answer yes to that question. Most Christian academics would be very hesitant to say one could do it.

Does that seem strange?

Actually, there are some very good reasons why academic historians—even those with a deep Christian faith–do not think we should wade into these waters. Frankly, it can be arrogant (and thus sinful) to claim that one can fathom the ways of God in the wider world. Historians are well aware that Christian Yankees and Christian Confederates during the Civil War each claimed that they could see God at work in the war, but those claims nearly always tried to prove that God was on their side and against the other side. Historians also know that other Christians, like the Puritans, stumbled over themselves trying to determine what counted as God’s favor, what counted as God’s judgment, what counted as Satan afflicting the faithful, and what counted as Satan fooling people into thinking their prosperity was God’s favor when it was really Christians sinfully putting trust in their own goodness instead of God. It got messy.

Furthermore, academic historians who try to piece together history from thousands of incomplete, complicated and conflicting primary sources know that figuring out what caused what in history is actually a tentative and uncertain business–even when we don’t try to bring in questions about the hand of God into the picture. Good historical methodology is based on making careful judgments based on the evidence we have before us. How in the world could we determine what counts as evidence of God’s activity? This is complicated by the reality that Christians have different theological explanations for how God works in the world.

Finally, the “rules of the game” for historical scholarship declare that we should stick to evidence and assumptions that all historians can observe and agree upon, regardless of their religious or intellectual commitments. History is not a discipline, it is assumed, that can address theological questions.

And yet.

And yet, as a Christian historian, I am not fully satisfied with how we do things. Now, I’m not quite what to do about it. But I am curious about these questions.

For instance, it seems to me that we humans yearn for a grand purpose and direction in our existence and this comes out in the stories we tell, including our academic histories. As a result, we consciously or unconsciously end up trying to tell stories that fit into a master narrative that in some way mimics, approximates or searches for the hand of God.

Take James Bond. OK, it seems odd to look for the hand of God in James Bond films. Bond operates in thoroughly secular world. One can’t find God, Christian faith or any kind of religious practice anywhere. Furthermore, these films seem to be little more than entertainment. The vast majority of viewers don’t think very deeply about James Bond films and the film makers probably didn’t think very deeply about what they were doing, either. It may be pushing it to look for any larger meaning here.

But millions of people find these films to be interesting stories. Why is that? I would suggest that a good part of the reason is that we know that James Bond will not fail. Yes, there will be set backs and tight spots. He’ll get conked over the head a few times. But he always comes out on top by the time the closing credits roll. And we all know it.

The problem is that no human can go through life with Bond’s success rate. We can try to fool ourselves into fantasizing about being clever, witty, sexy, technologically astute and successful like James Bond, but we’ll never live up to his fictional example. But I don’t think Bond’s appeal normally lies in viewers imagining themselves to be like him. Instead, I would suggest that there is a reason why stories in which good triumphs over evil are so popular. It is because, consciously or unconsciously, we yearn for a Savior who can defeat evil and make everything right in the end. Temporarily, at least, James Bond makes us believe that evil will be overcome.

What about Samuel Sharpe? He was, after all, a living human being and not a fictional character. How do we tell his story and what meaning do we take out of it?

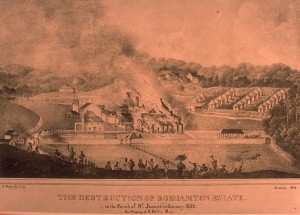

Here is what I find so interesting about Samuel Sharpe: he failed. And he failed spectacularly. His rebellion was quashed. He was executed. So were many of his fellow rebels. That is about as final of a failure as one could imagine.

But as I pointed out earlier, the low level of violence and ultimate failure of the rebellion helped convince a significant number of Brits that blacks were not animalistic savages. This reality played an important role in the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

We don’t have a lot of documentation to know what Sharpe was thinking, but I don’t see how he could have predicted how his rebellion would play out. I think it is safe to say that even though Sharpe probably calculated that a low-violence campaign would help his cause, it seems absurd to think that he figured that a quashed rebellion and his own execution would produce a favorable outcome.

Stay with me, here. Maybe, just maybe, the structure of those events make it possible to see the hand of God in this. All people of good will today, whether they are Christian or not, can agree that the abolition of slavery was a good thing. Christians, more specifically, believe that humans cannot make things right by their efforts alone. We believe we all stand in need of God’s grace, which in different ways trumps our flaws, failures, sins and evil intentions. The central story of the Christian faith is that God Himself came to earth and was crucified by humanity, but then rose again, overcoming death. The most important story of the Christian faith is a story of God bringing good out of the flaws, failures, sins and evil intentions of the world.

One can, of course, find plenty of flaws, sins and evil in the system of slavery. Historians also know that the entire process of abolishing the transatlantic slave system was a large, complicated, multi-faceted process that involved different nations, economic forces, social trends, cultural shifts, and political interests. No person or group or nation could control the outcome. We also can identify a number of people who were seeking God’s grace to deal with this oppressive system. One of those individuals, Samuel Sharpe, failed spectacularly in the process. And then good came out of it.

Can we say that this is evidence of God at work in history?

I’m interested to hear what you think.

At any rate, it beats James Bond.

Score:

James Bond 2

Samuel Sharpe 2