It’s that time of year again, when everyone in our society begins to obsess about two critically important decisions in life: 1) how can we outflank the other aggressive shoppers on Black Friday and 2) what specific thing to be thankful for on Thanksgiving. (Actually, wouldn’t the world be a much better place if we all put as much energy into the latter as we do the former?)

If you obsessing about the shopping part, I’m afraid I can’t help you. You and the other 4538 crazed shoppers who descend on Walmart on Friday morning (Thursday night?) will just have to fight it out among yourselves.

However, I have something new and different for you to be thankful for: humility. Not your own. You can try to be thankful for that, but it won’t work, for some reason. No, I mean the humility of good people who have gone before us. They have given a great gift to us.

How? Consider the abolition of slavery. Several years I posted a piece about how we all ought to be thankful for those who worked to eliminate slavery. Because of them, slavery is not only illegal in American society, but we all actually believe slavery is wrong. We have all inherited that idea. We did not come up with it ourselves. We don’t get any credit for taking a stand on that one, folks.

It’s hard to believe, but through most of human history, nobody thought that slavery was an institution that people ought to be actively campaigning against. Slaves, of course, hated the system and wanted to get away. A number of people thought it was bad. But they saw it as an unfortunate part of the world that we all had to live with, like poverty.

And then, in the early eighteenth century some people actually got this crazy idea that slavery violated God’s intention for the world and that God wanted them to do what they could to eliminate it.

Now, I admire William Wilberforce, God bless him, but he did not actually single-handedly abolish slavery and he didn’t start the whole thing. Decades before he came on the scene, some other people got the ball rolling.

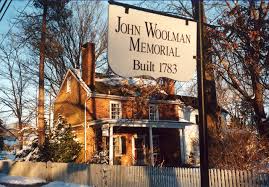

One of those persons, whom I think historians and Christians alike have not paid enough attention to, was a man named John Woolman. (I’m guessing you’ve never heard of him unless you are a Malone University alum who remembers Woolman dorm. Even then, the name might not have even meant anything to you. Sigh.)

Woolman was a Friend (Quaker) from New Jersey who became convinced that he needed to do what he could to convince others to give up slavery.

So, if you were John Woolman with this crazy idea, how would you do it? Would you debate slaveholders and convince them through evidence and the superior power of your reasoning that they were wrong?

No. And here is bad news for those of us who love to post on Facebook. Or, (ahem), write blogs. Argument and debate rarely ever change anybody’s mind. The only time argument really works is when all involved are less concerned with scoring points and more concerned with wanting to try to gain deeper understanding, which includes a willingness to consider that one might be wrong about something or other. That doesn’t happen very often.

Here is where humility comes in.

Before going out to discuss slavery, John Woolman prayed that the Lord would strengthen him and help him set aside “self-interest.” He confessed in his journal that often when he went to speak to others, he realized that he himself was guilty of desiring things for his own benefit. (Scoring points, perhaps? Greater holiness? Superior grasp of the truth?)

And then, do you know who Woolman went to talk to? Fellow Christians. Fellow Quakers, in fact. When he addressed them, he spoke of how they all needed to work together in “brotherly love.” They should all “promote the pure spirit of meekness and heavenly-mindedness.” He pointed out that they all needed to be “truly humbled as to be favored with a clear understanding of the mind of truth.”

And then he urged them to put aside their self-interest and consider what it is that God wants.

Hmm.

Prayer. Self-searching. Confession of one’s own selfishness. Seeking meekness. Admitting that one does not always see the truth clearly. Showing brotherly love with those one disagrees with.

Humility.

I don’t know why those of us who are Christians should be surprised by this, but I think if we were honest with ourselves we would have to admit that the most surprising thing of all is this:

It worked.

Over a period of a couple of decades, the Quakers managed to eliminate all slave-holding among themselves. Not only that, they had an incalculable influence on non-Quakers who worked against slavery: former slaves, evangelicals, William Wilberforce, and secular-minded abolitionists who followed them, just to name a few. Woolman and his Friends started the movement.

Over a period of a couple of decades, the Quakers managed to eliminate all slave-holding among themselves. Not only that, they had an incalculable influence on non-Quakers who worked against slavery: former slaves, evangelicals, William Wilberforce, and secular-minded abolitionists who followed them, just to name a few. Woolman and his Friends started the movement.

Let me point out that it was not just John Woolman who demonstrated humility. Perhaps we should give even greater credit to the Quaker slaveholders who voluntarily freed their slaves. They had to give up wealth and status to do that. And before they even reached that point, they had to give up something that we all hold on to even tighter: pride. They had to consider the suggestion that they were wrong. And then admit it.

So, yeah, there are a lot of things here we can learn for our own lives.

A place to start: on Thursday we should thank God that his grace worked through John Woolman, the other Quakers, and all the other people who were humble enough to actually admit that they were often selfish, muddled in their thinking, and did not love others as much as they should. And then that they went and did something with their chastened hearts.

We should be thankful for that. Because we have all benefited from their humility, even though we don’t really deserve it.