Happy Belated Columbus Day. Or Happy Belated Indigenous Peoples Day. Or Happy Belated Thanksgiving, if you happen to be Canadian.

Now I’m done with Canada for this post. Back to the United States.

Monday, of course, was Columbus Day in the United States — unless you happen to live in St. Paul, Minn., Portland, Ore., Albuquerque, N.M. or several other cities in the United States. Then it was Indigenous Peoples Day.

So what is going on here?

Well, in addition to finding an excuse to sell mattresses at half-price, we Americans use our holidays to remember history in particular ways. For about two centuries, we told the story of Columbus as a way to try to explain something about American character, even though Columbus never set foot on any territory that would eventually become the current 50 states.

(Columbus did land in Puerto Rico, so we do have a US territory to geographically connect us to the man. Interestingly, Caribbean and Latin American nations have not historically honored Columbus like the United States has. But that’s a different post.)

Americans have honored Columbus for quite some time. Since 1792, in fact. Columbus symbolized progress, the discovery of new knowledge, and a liberating break from old restrictions. So, rightly or wrongly, he entered our historical consciousness as someone fundamental to American identity. In 1836, for instance, Congress commissioned a large painting of Columbus’ landing for the US Capitol building. You can still see it there.

In the late 19th-century, Catholics had additional reasons to praise Columbus. Christopher Columbus was Catholic, a historical fact rarely highlighted by wider American society. This was important because at that time, Catholics were seen by many Protestants as a threat to American democracy. They argued that the Roman Catholic Church was hierarchical. It did not believe in the separation of church and state. Catholics believed that only priests could interpret the Bible properly. Because the nineteenth century was an era when the Bible was frequently read in public schools, Catholics often set up their own private schools, rather than have their children subject to instruction and biblical interpretations from Protestant teachers.

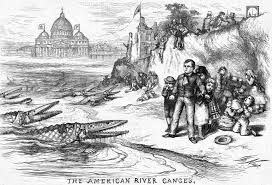

Wait, are those crocodiles coming ashore to eat our defenseless American children? No, don’t be silly. Look closely. Those are Catholic cardinals creeping up the beaches. Well, now. That makes a lot more sense, doesn’t it? (A Thomas Nast political cartoon from 1871).

In response, Protestants believed Catholics were undermining public education and, with it, the character of the American republic. Many Protestants formed organizations to limit Catholic immigrants. Anti-Catholic Americans even formed a political party in the 1850s, the Know-Nothing Party, to try to keep Catholics out. The Know-Nothing party dissolved in the sectional conflicts that led to the Civil War, but by 1890s, the impulse was back. The American Protective Association was established to limit Catholic immigration.

Columbus, of course, was also Italian. Immigration from Italy increased noticeably from the 1880s to the 1920s and this, too, provoked a backlash from many native-born Americans. Italians were perceived as dirty, prone to crime, (Mafia stereotypes abounded), and a people who did not mix well with surrounding communities. These characteristics would undermine democracy, it was thought, so a bunch of Harvard grads formed the Immigration Restriction League in 1894 to try to keep these “criminals” and other undesirable immigrants out. If Donald Trump had been around then, he would have been a founding member.

And then there was anti-Italian racism. Yes, Italians were actually thought to come from a separate race. In the scientific thinking of the day, there were three separate races under the rubric of the white race: Teutonic (which included Anglo-Saxons), Alpine and Mediterranean. Take a big guess who the genetically superior and the genetically inferior groups were in this scheme.

The founder of the Immigration Restriction League put it this way: Americans must decide whether they wanted their country “to be peopled by British, German and Scandinavian stock, historically free, energetic, progressive, or by Slav, Latin and Asiatic” (meaning Jewish) “races historically down-trodden, atavistic and stagnant.”

This form of racism had consequences. Organizations like the Immigration Restriction League campaigned for immigration restrictions based on race. They succeeded. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 put quotas on immigration from different countries, with the biggest limitations placed on nations with “Latin” and “Slavic” races. Immigrants from southern and eastern Europe faced greater restrictions than immigrants from the more favored “Teutonic” races of Scandinavia, Germany, and Great Britain. In the late 1930s, those immigrant restrictions, the racially-based thinking behind them, and the economic anxieties of the Depression led Americans to refuse to accept any sizable number of Jewish immigrants from Germany and Austria, despite Hitler’s willingness to ship them out of his nation. Ouch. Racially-based immigrant restrictions lasted until 1965.

So Italian-Americans had anti-racist reasons to campaign for Columbus Day. So did Irish, German, Italian, and Polish Catholics. After all, if Anglo-Saxons could celebrate an Italian Catholic like Christopher Columbus as a hero for the American nation, wouldn’t they be more likely to accept Italian-Americans on an equal plane? Wouldn’t this prove that one could be fully Catholic, fully Italian-American and fully American at the same time?

In 1892, on the 400-year anniversary of Columbus’ famous voyage, an Italian-American named Carlo Barsotti pushed for national recognition of Columbus. Building on existing affection for Columbus in the nation, Italian-Americans held massive rallies every year on October 12 (the date Columbus hit land in the Caribbean). They had deeply personal reasons to convince fellow Americans to recognize Columbus as a true American and a hero. By World War I, New Jersey, New York, California, and Colorado (all states with significant Italian-American populations) had made Columbus Day a state holiday. By 1921, thirty states had followed. FDR proclaimed it a national holiday in 1937.

Oddly, despite the growing embrace of Columbus Day, Congress still passed racially-based restrictions on Italian and Eastern European immigration. Most Americans see what they want to see in their historical figures, and many Americans wanted to see a bold adventurer who discovered new lands, not an Italian Catholic who represented the immigrant dimensions of American society.

Nevertheless, the creation of Columbus Day was driven primarily by those who faced racism and wanted full and equal acceptance into American society.

Fast forward to the 1990s. While I was a graduate student at the University of Notre Dame, the Native American student organization on campus organized a protest against Columbus. They were particularly disturbed by a series of massive paintings depicting the life of Columbus that lined the hallway of the Administration Building (the one with the “Golden Dome,” which we alumni hold with such affection.) The Administration Building, with its paintings of Columbus, had been built in 1879, just when anti-Italian and anti-Catholic sentiment was beginning to rise again. For the Native American students in the 1990s, however, Columbus symbolized European destruction of their people.

The anti-Columbus cause, then, was driven primarily by those who faced racism and wanted full and equal acceptance into American society.

I’ll let you savor that irony for a moment.

OK, that’s enough of that.

Because I think the Native Americans have a point. Italian-Americans faced discrimination and prejudice, but not nearly on the scale or with as profoundly difficult consequences as Native Americans have faced. (I trust you are knowledgeable enough on this point that I don’t have to list or describe the historical injustices that Native Americans have endured).

I’m perfectly fine with changing Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples Day. We Americans already celebrate progress, the discovery of new knowledge, and a liberating break from old restrictions every time we upgrade our iPhones. Furthermore, Italian-Americans today are thriving in America. They enjoy full acceptance, and do not face any structural racism that confounds their daily lives. The same cannot be said of Native Americans.

Plus, we’ll always have Columbus, Ohio. Just like Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in “Casablanca” will always have Paris. Only not quite as romantic.

There is a historical and theological point here, too. Indigenous Peoples Day would remind us of our national sins, while recognizing the dignity of a segment of American society that has often been pushed to the side. Confessing our historical sins can be a healthy thing, provided we also accurately recognize our historical virtues, which does not seem to be a problem for most Americans.

In fact, it can be a virtue to honestly and soberly face and admit our national sins. Those of us who are Christians ought to understand this on a deep and profound way. As with individuals, nations that fail to admit their sins end up falling into disordered, harmful behaviors. Ignoring our historical sins can lead us to imagine ourselves to be a people without fault. Having mis-diagnosed the past and our national character, we can end up blaming problems on something or somebody else. Believing that we pretty much have everything together, we can fail to take seriously those who point out issues of injustice.

This is actually a difficult thing to do as a nation — most nations only face their historical sins when they are forced into it politically (more on that in my next post).

We’ve overcome racism (conceptual and structural) faced by Italian-Americans. Great. So throw out Columbus Day. Let us face the more difficult cause of overcoming racism (conceptual and structural) faced by Native Americans. Bring on Indigenous Peoples Day.