(This is Part 4 in a series of blogs I am doing entitled “Why It Doesn’t Make Economic Sense to Run Education like a Business.”)

A story. During my first semester at Malone I was asked to teach a course in European history. The problem was that I had little graduate training in European history. But the department was going through some transitions and we did not yet have a historian in European history, so I was tapped to fill in.

This made me rather nervous. I felt a bit out of my depth. I worried that the students wouldn’t get what they needed. Furthermore, I wanted to make a good impression on the students and the department, since it was my first semester at Malone. And I knew that students would be filling out evaluations of my class at the end of the semester.

The result?

According to the student evaluations, this was the best class I ever taught. The scores were higher than just about anything I have taught in the fourteen years since then. Whew. Happy ending!

Wait a minute.

Why did I receive the best scores for a course that I was least qualified to teach at a moment in my career when I was least experienced as a professor? Have I regressed as a professor since that glorious moment in the fall of 1999? Do I really do a worse job in subjects that I know and understand the most?

No.

I know what that European history class looked like from my end, particularly in comparison to other classes I taught. Since I didn’t have much graduate school expertise to draw upon, I dipped back into my old materials when I taught European history in high school. I pulled out some old stories and jokes that I used to use, which was fun. More tellingly, I did not require as much critical thinking, ask as many challenging questions, or raise as many difficult issues as I did in my other classes. And I did not feel that I could grade as tough as I did in other classes, because I believed I would be punishing students for my lack of experience and expertise in this area.

In other words, this may have been the easiest, least challenging class I have ever taught in college. But from a customer service standpoint, it was a big hit.

And that helps explain why customer service is bad for the student.

Before I go further, allow me to pull out an old professorial trick here by saying that I need to qualify Case’s Law # 2.

Before I go further, allow me to pull out an old professorial trick here by saying that I need to qualify Case’s Law # 2.

There is a type of “customer service” in which professors care deeply about the academic excellence, character development and well-being of their students. They might even tell a few jokes in class.

That kind of customer service, however, runs on different dynamics than our economic model of customer satisfaction, which is built upon that old American motto, “the customer is always right.” That motto, which was popularized by department stores like Marshall Field in the early part of the twentieth century, was intended to inspire employees to do what they could to satisfy customers who were buying skirts and shoes.

Education, though, is a different animal.

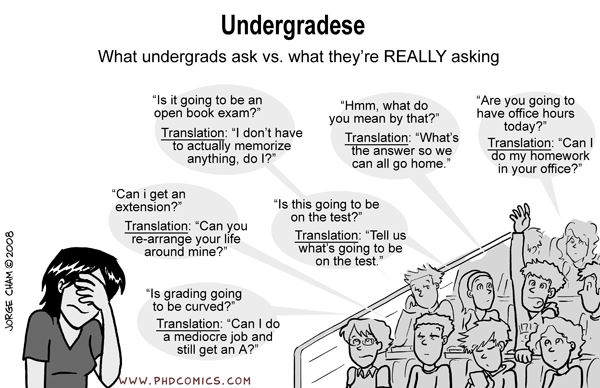

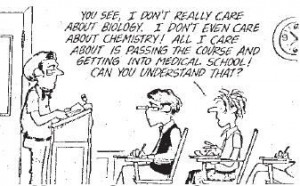

The department store model of customer service encourages professors to look for ways to grant short-term happiness to students. The easiest way to make most students happy in the short term is to make the course easy and hand out good grades. Professors know this. Consider the following, from an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education of September 5, 2008:

“For faculty members, the pressure to grade generously comes not only from anxious students and ‘helicopter’ parents, but also from promotion-and-tenure committees that look carefully at end-of-term student evaluations. ‘It’s easier to be a high grader,’ says (one professor). ‘You can write that A or B, and you don’t have to defend it. You don’t have students complaining or crying in your office. You don’t get many low student evaluations. The amount of time that is eaten up by very rigorous grading and dealing with student complaints is time you could be spending on your own research.’”

What we have here is a variation on Barlow’s Law. This is why we need to understand grade inflation better – the data that shows that grades in higher education have been getting higher and higher in the past four decades. Some observers say that it is not a big deal and a few people even say it doesn’t exist. But most observers and their studies indicate that it is real and it is a problem. That means we need to think more carefully about these things.

A hypothesis: our academic standards have gradually eroded over the past few decades because we have treated education more and more like a business. I don’t know if that is true or not, but I would like some good researchers to investigate it.

Another qualification: student evaluations do tell us some things. They are blunt but helpful tools for identifying real problems in the classroom. At the end of the day, students want to believe that they have learned something, even though they may not want to be pushed very hard. Truly poor teaching does show up on student evaluations. In addition, some students truly desire to be pushed toward excellence and will indicate so on their evaluations.

But it looks like those good intentions only go so far. Even very good students who want to get into graduate school will complain that tougher grading (and presumably, the higher standards that go along with it) will hurt their chances to get into graduate school (where, ironically, they will face more challenging standards). Interestingly, these potential graduate students may be correct. A recent study actually shows that “admissions officers appear to favor applicants with better grades at institutions where everyone is earning high grades over applicants with lower grades at institutions with more rigorous grading.”

But it looks like those good intentions only go so far. Even very good students who want to get into graduate school will complain that tougher grading (and presumably, the higher standards that go along with it) will hurt their chances to get into graduate school (where, ironically, they will face more challenging standards). Interestingly, these potential graduate students may be correct. A recent study actually shows that “admissions officers appear to favor applicants with better grades at institutions where everyone is earning high grades over applicants with lower grades at institutions with more rigorous grading.”

Customer service: it lowers our standards and gives us the incentive to produce an inferior product.

Is that the economic model we want?