This post, which is a follow-up to my previous post, starts with a stolen anecdote. (Like preachers, I take my best anecdotes from others.)

Celia King, the Service-Learning Director at Malone, spoke in chapel the other day and explained how she once came across a big pile of clothes at an orphanage in China. And when I say big, I don’t mean big, as in 5-loads-of-laundry big. I mean big, as in somewhere between the size of a Ford Econoline Van and a fire truck. And speaking of fires, one of the orphans, under the instructions of the orphanage leaders, was busy torching this emergency-vehicle-sized-pile of clothes.

So, what was going on here?

It seems that a good number of kind-hearted folks had decided to help out the orphanage, so they organized a pretty efficient system for getting clothes to this orphanage.

The problem was that they were so efficient that the orphanage was soon flooded with far more clothes than they needed. The clothes piled up. Did I mention it was a big pile? The big pile drew rats. Rats, as I understand, are not good for orphanages. So they periodically had to torch the delivery-truck-sized piles of clothes that piled up.

Celia pointed out that it is great to try to help out when we see a problem, but sometimes we jump in without fully knowing the situation.

I would also point out that Americans are particularly susceptible to this problem, because we are shaped by a culture that is task-oriented. Since the colonial era, Americans like to fix things and accomplish tasks. We have built train systems, we have put a man on the moon, we have invented the Post-It Note, and we do more piles of laundry per capita than anyone in the world. Even the Dutch. (Or at least this was true in 1937). Millions of American schoolchildren have been inspired by Abraham Lincoln, who famously told the nation, “Git ‘er Done!” (OK, that wasn’t really from Abraham Lincoln, who was much more eloquent in his public speeches, but I still think it could have been Abraham Lincoln at the age of 19 as he hauled flatboats down the Mississippi River).

For instance, if Karen refugees suddenly arrived on the doorstep of our church, like they did in that Baptist church in upstate New York, (see my previous post) I imagine that many kind-hearted church members would jump right in to find them clothes, arrange transportation, set up English classes and get them to driving instructors. That would demonstrate a great level of compassion.

But would our churches know the best way to deliver these services to them? Would our churches know whether the Karen needed Bible instruction? Would our churches need to give them tips on reaching out to their unchurched Karen neighbors? Would our churches know what spiritual issues are most pressing to their community?

Maybe, maybe not. Actually, probably not.

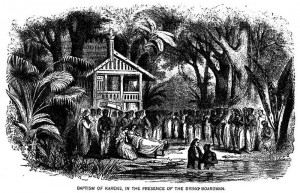

In addition to the desire to help, then, it is critical that we slow down, engage in conversation and listen. Especially in cross-cultural situations. For instance, if we were working with Karen refugees in our churches and wondering if they needed Bible instruction, we might learn through a discussion with a Karen leader that their great-great-great-great grandparents became Christians in the 1840s. We might also learn that their family had been reading the Bible, in the Karen language, since that time. So do they need Bible instruction? They might, they might not. They might want some theological education. But they might not. They might want English language instruction. But maybe only some of them. We would have to listen to them to find out.

The best missionaries and missionary thinkers in history understood this. Do our churches? Is listening built into the way we do our ministries? I hope so.