(It’s been a while since I’ve made a blog entry. Is this something I should apologize for? Explain? Try to justify? OK, here it is: I’m sorry about that. I’ve been flooded with papers to grade, institutional responsibilities, and scholarly projects that last few weeks……….

Hmm. They say you should never begin a speech with an apology. Maybe it’s the same for blog posts).

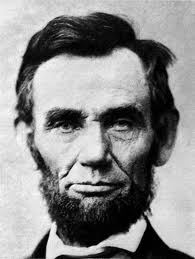

There are a number of reasons why Americans are fascinated with Abraham Lincoln. He was a key figure in one of the more critical events in American history. He

wore that funny stove pipe hat. He wrestled with significant political, constitutional, racial and social issues. He worked his way up from a log cabin to the White House. He was tall.

Most of this interest is deeply tied to our interest in the American nation. That interest is fine, but I’d like us to consider something else. While American Christians ought to be interested in the American nation, we ought to have a deeper interest in the Kingdom of God. But here is the problem: the Kingdom of God does not get a lot of play from Steven Spielberg, the History Channel, the Ford Motor Company, or our pennies. So we have to do some work to bring stories about the Kingdom of God into our consciousness.

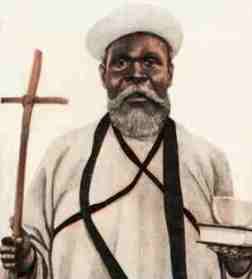

So let me make one small attempt to contribute to our interest in the Kingdom of God: you should know something about William Wadé Harris.

William Wadé (pronounced “waddy”) Harris may not be as historically important as Abraham Lincoln. But I would argue he’s more historically important than any number of American Presidents you have heard of, including Calvin Coolidge, James Monroe, and William McKinley. (Some folks here in Canton would grumble at me for that last one).

Why would I argue for Harris’s significance over a good Canton man and Methodist Sunday School superintendent like William McKinley? Besides the fact, that is, that the eight presidents from Ohio don’t exactly give us goosebumps?

Consider this: there are more Christians in Africa today than there are people in the United States. That development represents a significant change in world history. And that change is worth some consideration.

There are many aspects to this story, which covers several centuries, eight hundred people groups and more than fifty nations. William Wadé Harris, though, is as good a place to start as any.

Born in Liberia, Harris converted to Christianity as a young man and taught for an American Episcopalian mission for a number of years. Then he set off on his own.

Between 1910 and 1930 Harris traveled through what is today Ghana, the Ivory Coast and Liberia as an evangelist. Around two hundred thousand Africans became Christians under this ministry. His ministry also influenced and inspired numerous Pentecostal movements in West Africa, movements that have spread across the continent. That kind of influence in itself should make us sit up and take notice.

But I also think we should know about Harris and understand him better because his ministry raises a number of important issues related to the Christian faith, culture and power. For instance, many people today associate evangelistic missionary work with imperialism. Some anthropologists like Lionel Tiger do more than associate the two. He bluntly calls missionaries “frank imperialists.” Tiger’s camp assumes that any action that addresses the spiritual or theological issues of someone from another culture disrupts the “fundamental ideals and values” of those people. And there are many American Christians who, feeling uncomfortable with the idea of evangelism, take a similar stance. For many, evangelism seems somehow be an inherently intrusive, imposing and self-righteous activity. Interestingly, though, other forms of missionary work are seen as less intrusive and even helpful. Lionel Tiger, like most of the people in the “Frank Imperialist” school of thought, does not object to outsiders providing water projects, modern medicine or education to people from other cultures. He assumes that these actions do not disrupt fundamental ideals and values. (Don’t they? That assumption would be an interesting one to discuss some other time).

Tiger, and others, could use a better grounding in the history of world Christianity and the work of Harris, who operated without the guidance, support or direction of any missionaries. Many of his travels took place in regions where no missionary or white person had yet visited. In fact, ten years after Harris had itinerated through many inland villages in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, Methodist and Catholic missionaries were great surprised to arrive in villages to find thousands of Africans already claiming the Christian faith. (This dynamic occurred in many places in Africa). Would a ministry of a single African preaching to thousands of other Africans, far from the presence of Europeans, be considered imperialism, especially when these Africans voluntarily adopted Christianity? It is hard to square this historical reality with simplistic claims of frank imperialism.

And there is more to Harris. (What, for instance, is your stand on angelic visions?) I’ll bring up a few more cultural issues in my next post.

this book

this book