(Blogger note: This blog has fallen into a period of inactivity lately. Last semester was a particularly heavy semester for me and something had to give. That something was the blog. But I’m going to try to get it up and running again.)

It is hard to think clearly when one feels threatened, angry or anxious. Some of the stupidest things I’ve said in my life have come in the midst of Notre Dame football games. Consider, also, what war does to our thinking.

During the Civil War, it was common to find sermons like that from a northern evangelical minister who proclaimed that the conflict was between “the rebellion of a proud, luxurious, lascivious, unprincipled, murderous Absalom, against his noble, unsuspecting, too affectionate and over-indulgent father, David.” For their side, southern ministers preached messages such as, “the fall of Sumter…was a signal gun from the battlements of heaven, announcing from God to every Southern State this cause is mine.” Yep. Ministers were pretty clear about what God was up to, weren’t they?

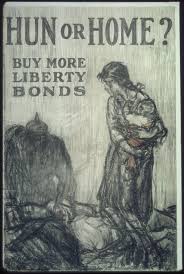

During World War I, Americans did not simply shun German culture by changing the names of “frankfurters” to “liberty sausages” or towns (like mine) from “New Berlin” to “North Canton.” War anxiety also led Americans into darker behaviors. A German immigrant in St. Louis was lynched. The US government depicted the Germans (these people who had produced Beethoven, Kant, and Einstein, to name a few) as barbaric “Huns” who were out to destroy civilization. Americans also eliminated German language instruction from thousands of schools because, apparently, if kids learn to speak German they’ll develop an irresistible urge to invade Belgium.

Of course, we all know that during World War II Americans became so anxious and fearful of Japanese-Americans that they were placed in internment camps. As a governmental official in California explained in justifying this policy, “the very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.” Right. And the fact that Ecuador has not invaded us to date is disturbing confirmation that they will.

We need to understand this about ourselves. Anxiety, fear and anger lead us to think in muddled ways that then lead to damaging behavior.

This is just as true today, when we feel anxiety, fear and anger over the recent terrorist attacks in Paris. Radical Islamists pose a real threat, of course. But just as Americans made sweeping stereotypes of enemies in the Civil War, WWI and WWII that led to unjust actions, we need to remember that we can do the same.

That is why I bring up the comments of fellow evangelical, Franklin Graham. Now, Graham does great work with Samaritan’s Purse and elsewhere, but I’m concerned about recent proclamation he has made.

They grew from a dispute at Duke University, when the institution decided to broadcast the Muslim call to prayer from the campus bell tower. There is a valid issue about whether or not it was wise or good for an occasionally Christian chapel at a formerly Christian university to do this. A healthy discussion could be given on that, but that is not what I am concerned about here.

Franklin Graham said this: “As Christianity is being excluded from the public square and followers of Islam are raping, butchering, and beheading Christians, Jews, and anyone who doesn’t submit to their Sharia Islamic law, Duke is promoting this in the name of religious pluralism.”

Here is the problem: Graham lumped millions upon millions of Muslims into one category of “raping, butchering and beheading.” The overwhelming majority of Muslims around the world (and in the United States) are not radical extremists. Most Muslims believe, theologically, that these terrorists are not true Muslims and that Osama bin Laden is in hell right now. It is true that most segments of Islam have a problem with the modern idea of religious freedom, and that is worth discussing. But to lump all Muslims together with terrorist groups because these groups claim to speak for Allah is the same as lumping all white Christians together with the Ku Klux Klan because they claimed to be defending the Bible and burn crosses in people’s yards.

This calls for clearer thinking and a more humble approach to this difficult and complicated situation. I understand that many Americans do not understand Islam very well, meaning it is easy to draw hasty conclusions from news bites and media stereotypes. It’s a problem for many Americans and many Christians. I’m saddened that Graham has fallen into this line of thinking.

Graham, I’m guessing, feels threatened from two directions. Like many evangelicals, he probably feels threatened by those who would like to sweep the public square of any religious references or who would like to try to relativize all religions in such a way as to depict them as essentially the same. Those are valid points. Like many people in the US, Europe and the Middle East, he probably also feels threatened by the horrendous actions of the extremist Islamic terrorist groups. That is a valid threat as well.

The really difficult part? Christians are commanded, by the grace of God, to love those they disagree with and those they consider their enemies. Prejudicial stereotyping comes from the anxious and sinful parts of our nature (a nature I share as well) not from the grace that has been given to us.

Realize also that I am not saying Islam and Christianity are the same. I would like to see Muslims come to Christ, just as I would like to see all people in the world come to a deep, full union with Christ. But the practice of lumping all Muslims together as terrorists is not only a really, really bad way to evangelize, it makes the work of evangelicals working with Muslims much more difficult. Unfortunately, statements like those made by Franklin Graham work against the evangelistic goals that his father represented in his life.

So, let us start by asking God to give us the grace to love better. The first step in loving somebody who is unfamiliar to us is to try to get to understand them better, which includes trying to see matters from their shoes. The Muslims I know about in northeast Ohio feel threatened and besieged and misunderstood in the aftermath of every terrorist attack that hits the news. Evangelicals ought to know what it feels like to be misrepresented in the media. From there, we might be able to better figure out what to do about such a complicated issue as Islamic prayers in the Duke bell tower.