The cold hard truth: we Americans love to believe there are easy solutions to complex problems.

Want to build a democracy in southeast Asia? If we were to believe Sargent Muldoon in The Green Berets, simply defeat the bad guys and write a Constitution. There it is! Happy Ending!

Right. In moments like these, it can be helpful to get some perspective from Monty Python. In this case it is an old sketch, “How to Do It,” satirizing a popular children’s TV show in Britain, in which they explain how to do all sorts of amazing things. It takes the Pythons all of thirty-four seconds to describe how to play the flute and rid the world of all known diseases. There it is! Happy Ending! (Yeah, click on the link above. It’s worth watching and it is short).

Come to think of it, want to fix America? Our political candidates will explain how to do it in one TV ad, which is about as long as the Pythons took to rid the world of all known diseases.

Gosh, the Pythons didn’t have to satirize a children’s show — they just as easily could have done the same thing with our politicians.

But before we get too self-righteous here (a great temptation when writing blogs or discussing politics or, heavens, doing both) keep in mind that most politicians know these problems are very complicated. They grossly oversimplify complex issues because they want our vote and we respond positively to those who give us simple solutions to complex problems.

Real life, of course, is complicated. Very complicated.

Take, for instance, the establishment of democracy. As I mentioned in my last post, the U.S. and the new Latin American nations had a number of important factors in common in the early 19th century. But it didn’t go well in Latin America. Between 1820 and 1990, twenty-two nations of Latin America wrote, implemented and scrapped between 180 and 190 constitutions (depending on how one counts them). Not sure what Sargent Muldoon would say about that.

Why do some nations develop democracies and others fall short?

It is complicated. Did I mention that?

Here are just a few things that the American colonies had going for them upon independence that Latin American colonies did not have:

- widespread literacy among ordinary people

- practices of religious freedom that had been established for decades before independence (Christians in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania getting a jump on this before Enlightenment thinkers caught on).

- not just capitalism, but a particular kind of capitalism in which land (critical for an agricultural economy) was available to ordinary people (if they were white). A while back I described how I have personally benefited from ancestors who took advantage of this situation, which would not have been possible in Latin America, where almost all the land was controlled by elites.

- a couple of centuries of political developments, conflicts (and a civil war) in England in establishing practices that divided power between the legislature and the executive. These developments produced…..

- a tradition of representative government (on local levels) that goes back 150 years before independence. Virginia got the ball rolling with the House of Burgesses in 1619 and every colony established a legislature shortly after they were founded.

And here is a rather odd and disconcerting factor:

- Racism in America helped extend democracy to (some) ordinary people, while racism in Latin America worked against extending democracy to ordinary people. How does that work? In essence the whites in control of new Latin American nations simply did not want to grant “consent” in government to ordinary people, because the majority of ordinary people in most places were Indian, black or mixed-race (mestizo). For instance, in an 1881 election in Brazil, 142,000 people were able to vote, out of a population of 15 million. That’s 1% of the population, folks. American founders were more willing to grant “consent” to ordinary people because a majority of Americans were white. The American founders did not, for the most part, extend government “of the people, by the people and for the people” to the people who were black or Indian. But the people of color were a minority, so they did not scare the American elites like the vast majorities scared the elites in Latin America. (A reminder that it took the United States a long time after 1776 to grant basic democratic rights and opportunities to people of color).

Not a pleasant historical point, but there it is.

And finally, a factor that does not have to be a factor:

- it has been common among many Americans to declare that one has to fight militarily to gain freedom and democracy. But Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several other nations have shown that it is possible to achieve democracy without employing soldiers to fight for it. So there is one factor that is often thought to be a necessary condition that is not necessarily necessary.

And I haven’t mentioned all the factors. In fact, you might know of other issues or factors that should be added in the mix.

Democracies are very, very difficult to develop.

So, what can we take away from this? Many things, but here are a few thoughts I have:

First, democracies take a long time to develop. Americans had at least a two-century jump on new Latin American nations in many of these areas. Americans are not superior to African nations because they are trying to achieve in fifty years what took America several centuries to achieve.

Second, we should resist supporting policies based on oversimplifications. The United States has sometimes underestimated these complexities. The Vietnam War showed that it was very difficult to “win the hearts and minds” of the people. In 2003 the U.S. invaded Iraq and defeated Saddam Hussein and his military in about three months (which was what the U.S. military had calculated). However, our government did not have an effective, or even well-developed plan for how to help Iraq move to democracy after Hussein was gone. We sort of assumed the Iraqis would just embrace freedom. A long, painful and protracted civil war followed that ensnared us since, well, we helped create the disorder that produced it. So, think carefully about simple promises that we can bring freedom to other places in the world.

Third, if you think about the factors above that helped establish democracy, you will see that many are built on ordinary people doing what is good and right in caring about other people, even if they are quite different from themselves. Teachers teaching. People of faith, and business people and politicians working to ensure that all people have economic opportunities. Ordinary people granting respect and freedom to people of different religions.

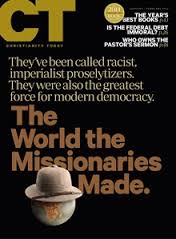

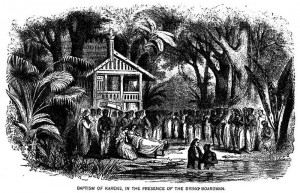

In fact, a number of months ago I mentioned a ground-breaking study by Bob Woodberry that shows that the work of missionaries in history has actually helped build democracies around the world. So, we should support our missionaries, our non-profits and those who are serving others particularly the “widows and the orphans,” as the Bible reminds us regularly. We should do it anyway, but we can add the development of democracy to our list of motivating factors.