The Brits are a funny people.

Yes, they are humorous: Monty Python is proof of that. And I could tell you stories about a couple of my British friends who make me laugh.

But I’m thinking of a different kind of funny. I mean funny as in a bit strange. And I could tell you stories about a couple of my British friends who…well, no, let’s not go there.

Instead, let’s go here: the British are funny because their government actually pays the leader of the party that loses the national election. They give her or him a post in government with a salary equivalent to a cabinet member. This person gets a car and a paid staff. The loser.

It is both “funny ha-ha” and “funny strange.”

And yet…..it is crucially important for the successful operation of their democracy.

The Right Honorable Jeremy Corbyn: Labour Party leader and the current Important Loser — OK, Her Majesty’s Official Opposition –in Great Britain right now

The official title for this person is “Her Majesty’s Official Opposition.” That title encompasses an idea, “loyal opposition,” that is not used in the U.S. very much. That is why it may seem funny to Americans.

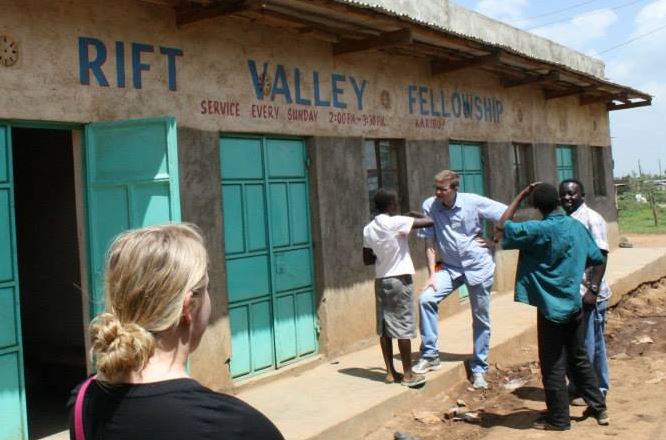

But there is something very important here. Back in 1992, when I found myself observing the political strife around me in Kenya, I heard the U.S. ambassador to Kenya give a speech in which he said that a problem Kenya was dealing with was that they did not have a tradition of a “loyal opposition.”

That phrase has stuck with me ever since. What is it?

The concept of the “loyal opposition” actually encompasses many things. Among them lies the thinking that disagreement is legitimate, that dissent is a healthy part of democracy, and that political opponents should not be treated as enemies to society. In 1937, Great Britain went so far as to officially create this position, to protect dissent in their parliamentary system.

Putting up with dissent is not easy, though. In fact, because of our sinfulness as humans, I would argue our default mode is to try to ignore, silence, or even eliminate those who disagree with us. People in power don’t want to have to listen to those who criticize them.

This is one thing that makes building a democracy so difficult. When Kenya got its independence in 1963, it had to build a nation from more than thirty different ethnic groups. Fearing division and fragmentation, the leaders created one political party, KANU, that was supposed to encompass all people. They effectively outlawed all other parties. The result was that Kenya did not develop healthy practices of dissent and disagreement in politics. Political opponents, journalists and protesters were jailed if they got too critical. Some were killed in mysterious circumstances. Those in power solidified their grip on the system. After thirty years, the nation had a grand total of two presidents and the first, Jomo Kenyatta, only vacated his post because he died. During the 1992 elections, a time when I was wondering if my family would have to be evacuated, political strife ran deeply because opponents were pushing for an alternative party. The ruling party, KANU, saw these dissenters not only as a threat to their power, but as enemies to the nation.

Unlike those funny Brits, the United States does not officially have a position of loyal opposition built into its system It does, however, have many of the principles embedded in other ways. Checks and balances ensure that one branch of government will be able to disagree and even block another branch. The federalist system of dividing power between the national government and state governments is another way of doing that. The Bill of Rights guarantees rights of assembly, speech, religion and press, thereby implicitly promoting dissent.

But it was not easy to establish practices of loyal opposition.

The clearest example of this were the Sedition Acts. In 1798 — after the Constitution had been in effect for more than a decade — the Federalist faction in Congress passed laws that leveled fines and imprisonment for anyone writing anything “false, scandalous, and malicious against the government.” President John Adams, a Federalist, signed it into law.

A newspaper editor, Thomas Callendar then wrote “the reign of Mr. Adams has, hitherto, been one continued tempest of malignant passions. As president, he has never opened his lips or lifted his pen without threatening and scolding. The grand object of his administration has been to exasperate the rage of contending parties, to calumniate and destroy every man who differs from his opinions.” He was fined $200 and jailed for nine months.

Another newspaper editor, Luther Baldwin, wrote that he wished that a cannonball that had been fired in honor of Adams’ birthday had landed instead in the seat of his pants. Baldwin was fined $100.

Some politicians thought Adams’ opponents really were enemies to the nation and threats to democracy. And they tried to silence them.

When you think about it, these are the kinds of shenanigans that we think about happening in many African or Latin American nations. Or Russia. Or Egypt. Or Turkey. Or Myanmar (if you think about Myanmar, that is).

Fortunately, the United States worked through it, for the most part.

John Adams made a grave error by signing the Sedition Acts into law, but he later did something that was crucial for American democracy: he lost. More importantly, he lost well. In the 1800 presidential election, he was defeated by Thomas Jefferson, who was supported by a different faction, the Democratic-Republicans.

And what did John Adams do? He left Washington DC and went back home to Massachusetts.

To those of us steeped in stable democracies, this is such a typical, “normal” thing for a politician to do, it doesn’t even seem notable. (Our lack of surprise is one of those Good Things that we don’t realize about ourselves.)

Consider this, though: it was the first significant peaceful transfer of power in modern times. Adams did not try to take over the military. He did not claim voter fraud. He did not arrest his opponents. He did not try to change the Constitution in ways to keep him in power. Those are all things that politicians facing electoral defeat have done in many places in the modern world.

Adams knew how to lose. It was, in my estimation, his greatest moment.

Thomas Jefferson should get credit, as well.

In a rather famous inaugural address in 1801, he said, “we are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” He meant that the loyalty to the democratic system should be greater, than loyalty to one’s party or political allies. Meanwhile, dissent was critically important. “All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable,” Jefferson declared, “that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression.”

The Sedition Act had punished Jefferson’s allies. But in 1801 he did not try to arrest his opponents as payback. Jefferson did not try to pass a new set of Sedition Acts (which had expired) to silence the opposition. He did not turn to the military to solidify his power.

Jefferson knew how to win in a manner that was healthy for the nation. Believe it or not, I seriously think that this was his finest moment — maybe more so than that Declaration thing.

We need to keep the loyal opposition idea in mind. In a rather crazy election year when passions and anger seem to be running more deeply than in the past, in an election when many are behaving badly, let us remember that there are principles that are higher than our particular candidate, our particular party and our particular political issues.

Those funny Brits are on to something, after all.