(I have another post coming on “privilege,” but first, this news about college costs.)

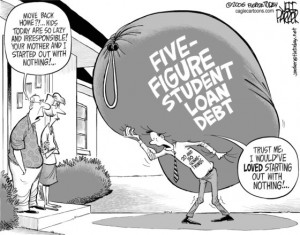

Staggering student debt from college……is mostly a myth.

What? Hasn’t a college education (especially at private colleges) become outrageously expensive in recent years?

Not really. What actually may be going on is that our our culture has bought into perceptions that just aren’t accurate.

If you care about the Christian faith, you should care about this. Many Christian colleges (and non-Christian private colleges) are facing financial challenges because fewer students are going to these kinds of colleges. I think that a major factor here (although I don’t have hard evidence for this) is that many Christian students and parents are steering away from Christian colleges because they believe the financial costs have become unbearable. So, the thinking often goes, better to go to a public university or a community college. College grads going to a private institution will be drowning in debt for years, Right?

Wrong — at least for the majority of students.

I’ve supplied evidence on this issue before, but now we have more. The problem is that anecdotes and simple images (the story of the college grad with $80,000 dollars of debt, for instance) gets lots of media play and the hard evidence does not. The Brookings Institute has released a study showing that the Staggering Student Debt cliche is actually a perception that has taken on the status of myth. They don’t phrase it quite like that, but that is the upshot.

If you don’t want to read the whole article, here are a few highlights:

— Average tuition at private colleges (non-profit private colleges, that is) has not increased any faster than inflation over the past decade, once you consider financial aid. (My commentary: the standard tuition price you see really does not tell you how much you will pay. You have to receive a financial aid package to know what you will actually pay. It’s dumb, but that’s how the system works).

— Tuition really has increased at public institutions, by more than fifty percent.

— The amount of income the average grad has to devote to student debt is about the same today as it was in 1992 and it is actually lower than it was in 1998. How can that be? Average student debt has actually risen in the past two decades, but so has the average income of college grads.

Ha, ha, this is funny. But do you think we do better in trusting a cartoon or a evidence from the Brookings Institute?

— Large student debts are uncommon. 58% of all grads have less than $10,000 worth of college debt. Those with Staggering College Debt are outliers — only 7% have more than $50,000.

— Students from financially well-off families are paying more for college. Students from middle and lower income families are not.

— The real problem comes for those students who drop out of college without a degree. Their debt has doubled over the last decade.

My thoughts:

1) Compare student debt to the average debt from buying a new car, and suddenly the costs of college do not look as scary. Consider this: last year the average amount Americans borrowed to buy a car was $27,000. But most grads have student loan debts of less than $10,000. We Americans are going into much more debt for new cars than for college! Where is all the hand-wringing about the staggering load of our car debts? A college education is a much better investment, even if you only thinking in crass economic terms.

2) Students need to stay in college and see it through. For some students, that is a real challenge, for a variety of reasons. It is a challenge for those of us in higher education who are trying to help them persevere.

3) Secular colleges and universities present a particular kind of education, framed by secular assumptions, questions and goals. This can be helpful, though it does not often require students to think about important questions in life. Christian colleges do more. They frame their education by the assumptions, questions and goals of the Christian faith. That is a different kind of education. It is not interchangeable with the kind of education you get at a public education.

So if you know of a Christian who is considering college, bring up the issue of misperceptions about student debt. And raise the question about what a Christian education does differently than a secular education.