Mother’s Day is fast approaching, and that means we Americans are all busy spending money, just like we do with every holiday. The latest estimates show Americans will spend $20 billion on Mother’s Day items this year, surpassing both Halloween and Easter.

I am sure you sense a critique coming, but before I launch into it, I have to confess that I am not a very good gift-giver. What is worse, I haven’t always been as appreciative to my mother or my wife as I should be (on Mother’s Day or at other times). So the questions about consumerism and holidays that I raise do not stem from my own virtue and righteousness. Let me draw from some others.

First, it is worth noting that we Americans tend to turn every holiday into a spending spree. I once met a fellow scholar from England who was visiting the United States over Memorial Day weekend. He found the idea of “Memorial Day sales” to be very curious. In Britain, Memorial Day (or Remembrance Day, as the Brits call it) is a somber event where one is supposed to honor and remember the many who have died in war. It is serious business. Why, my British acquaintance more or less asked, do we Americans think we should use the day to sell mattresses at half price? Good question.

That raises the question of what consumerism does to the meaning, habits and practices of holidays. Admittedly, as far as our holidays go, there is probably less self-indulgence in Mother’s Day as others. It is more other-oriented than many. Still, the economics of the thing has a way of shaping the meaning of the holiday. Critics have argued that Mother’s Day is primarily an opportunity for florists, greeting card companies, restaurants and other companies to make a buck.

But has anyone ever been as ticked off about Mother’s Day as Anna Jarvis? Angered by the “greedy” businessmen who dominated the holiday, she called them “charlatans, bandits, pirates, racketeers, kidnappers and other termites.”

I like the “other termites” part. It’s a nice touch.

Why was Anna Jarvis so mad? Well, she pretty much invented the holiday. Then she watched American consumerism kick in and take it places she did not want it to go.

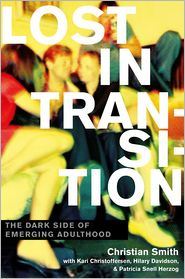

The story of the relationship between consumerism and Mother’s Day (and Christmas, Easter and Valentine’s Day) is told by Leigh Erich Schmidt in Consumer Rites: The Buying and Selling of American Holidays. (I received this book as a gift at Christmas one year — the ironies there make me happy).

Jarvis created the Mother’s Day International Association and convinced politicians, newspaper editors and church leaders to recognize the second Sunday in May as Mother’s Day in 1908. A dedicated evangelical who grew up as a Methodist in West Virginia, Jarvis intended the day to be grounded in the church, where mothers would be celebrated not only for their domestic duties, (which, of course, is primarily how middle-class Americans thought of mothers in 1908) but to encourage others in their piety and roles in developing spiritual qualities in children.

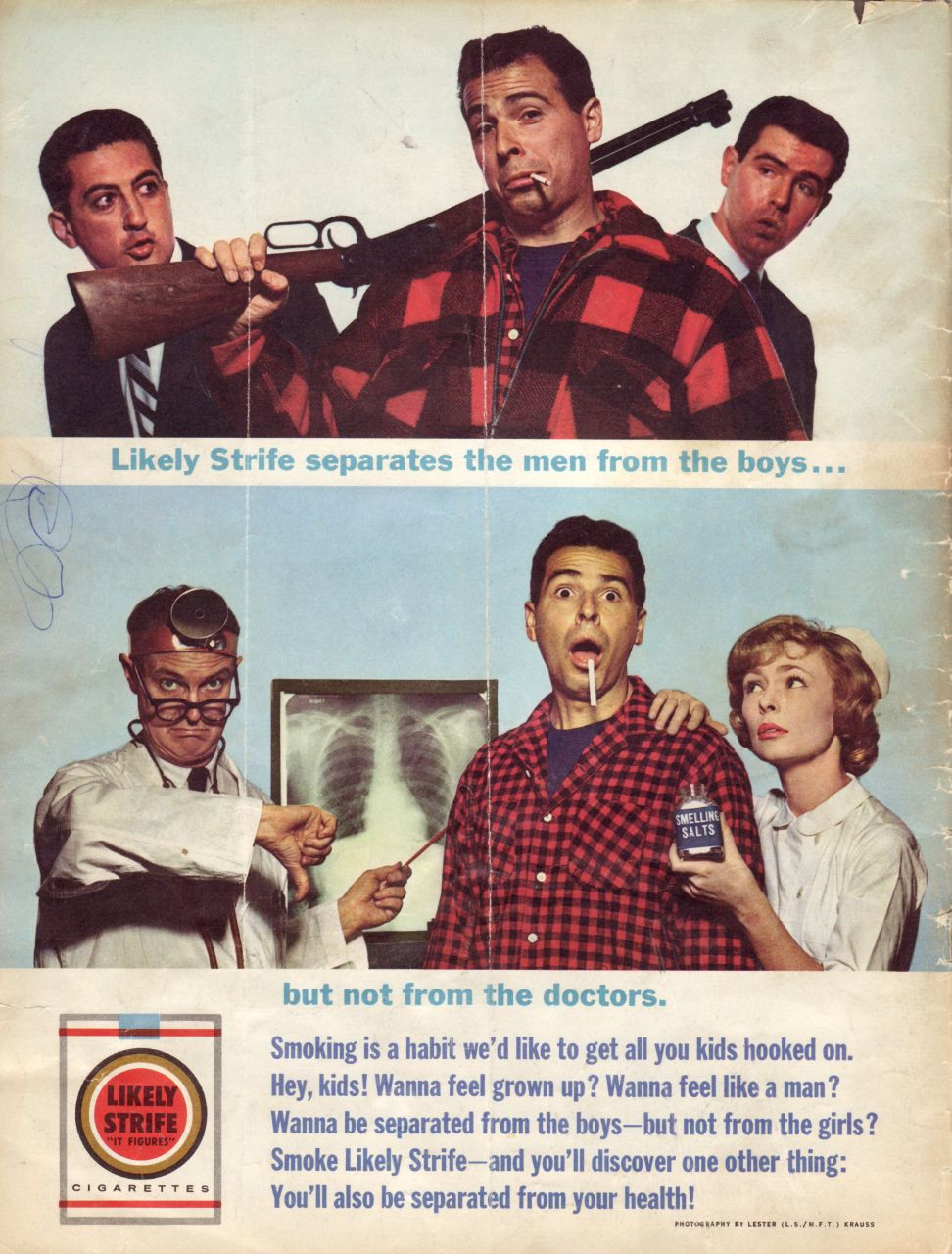

And then, unintended consequences. The very success of her movement ended up bringing her frustrations. Florists latched onto the day very quickly. Jarvis had suggested that people wear white carnations to honor their mothers, a simple recommendation that sent prices for the flower skyrocketing each May. By 1910, the floral industry began suggesting to customers that flowers also should be given to mothers as gifts. And then, well, what the heck, why not decorate churches, homes, Sunday schools and cemeteries with flowers on the holiday as well? Floral trade organizations encouraged aggressive marketing campaigns, while simultaneously advising their businesses that “the commercial aspect is at all times to be kept concealed.” Americans, of course, are suckers for good advertising. The catchy phrase, “Say it With Flowers” convinced many that spending money was the best way to express one’s affection for one’s mother. By 1920, the holiday had been so deeply entrenched in the world of consumerism, that Jarvis despaired that the meaning of the holiday had been hijacked by commercial interests. Hence the “other termites” thing.

I can understand Jarvis’ frustration. You may have noticed that consumerism bothers me somewhat. That is fallout from living in Kenya for six years and coming back to the United States with new eyes. Ever since then, I’ve been trying to figure out the implications of this system that envelops us. I have been a bit suspicious that Mother’s Day is often more of a Hallmark-driven holiday than a grounded appreciation for important people in our lives.

You can imagine, then, that I was a bit nonplussed a few years ago when a Kenyan friend of mine told me about an African pastor he knew who had introduced Mother’s Day into his church. This pastor had spent a number of years at a seminary in the United States and returned to Kenya with this idea. Inwardly, I groaned a little, worried that it would end up simply embedding consumerism and materialism into this African church.

I should have known, though, that institutions that get transplanted in the soil of a different culture don’t grow into the same kind of plant. Here is the situation: traditional Kikuyu men were socialized into ordering around their wives (and other women) to do tasks. Like many traditional cultures, the Kikuyu have a fair amount of patriarchy embedded in the way they did things. One expression of this patriarchy was that husbands would not show any appreciation to their wives. And that has all sorts of implications for how men and women related to one another, as well as how gender relations were structured.

We caught glimpses of this when we lived in Kenya. There were times in public places when African men — strangers — would approach my wife and tell her how she should be parenting our young children. And then expected her to act on those instructions. Right there.

It takes a village to raise a child and it also takes a village to get women to act as the men want them to.

But the Kikuyu pastor, as my friend explained, introduced Mother’s Day as a way to instruct the men in his congregation that they were not only to do something nice for their wives, they were to recognize that women were important and valuable. They were to tell their wives this and thank them for something they did. These actions were quite different for the Kikuyu men in that church. This pastor had not simply picked up the idea that Mother’s Day was about men buying flowers for mothers and wives. He saw that the Christian faith had implications for gender relations — at the very least, men should not lord themselves over women. There are far more implications for gender in the Christian faith than that, of course, but I find this a significant development for this church.

Whatever her flaws, (and she had them), Anna Jarvis would have been pleased, I think, with this Kenyan pastor. She understood that the way we related to one another mattered. Jarvis said that “any mother would rather have a line of the worst scribble from her son or daughter, than any fancy greeting card,” and she is probably right. A card can prevent people from actually thinking about and articulating what is important in a relationship.

I’m not anti-gift (nor was Jarvis). For many mothers, receiving gifts may be a meaningful way to accept the love of others. But there are other ideas out there besides those we get in our advertisements. Maybe we should think more deeply about whether gifts are the best way to express gratitude and honor those we love. A phone call, a note, time together, making meals…I don’t know. It probably depends. I’m not very good at this, which means I need to think about it more.

I’d be interested to hear about any non-consumeristic ways you have of handling Mother’s Day.