Boy there’s just nothing like reading the headlines, or turning on cable TV news, or listening to talk-radio, or clicking on your favorite internet news site to make you feel all warm and happy and peaceful inside.

Right.

More likely, we come away thinking, “Man, the world sure is a mess.”

It can take a toll on our soul. What to do about that?

Avoidance seems to be a popular option. We could go shopping, escape to a movie, or watch the NFL. (Well, the last one doesn’t work if you are a Browns fan).

Still, some of us know it is important to be engaged. But what to do when it all just seems so distressing?

Here is one small idea: take a careful look at history. Particularly the history of “news.”

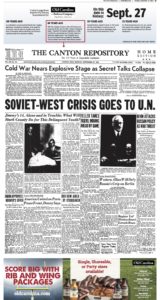

For the past year or so, my local newspaper, the Canton Repository, has been reprinting “A Page from History,” showing the Repository front page from the date in a previous year. They usually select a day that has some sort of news item that would be interesting to us. For instance, three recent days featured Vice-President Calvin Coolidge visiting Canton in 1922, how a local sheriff raided an illegal gambling den in 1911, and how Congress was trying to find communists in Hollywood in 1947.

I have this question. If we were reading the newspaper in 1922 or 1911 or 1947, what would we think about the shape of the world?

Here are the other front page stories from those dates:

October 27, 1922:

– A minister in Newark, New Jersey is accused of murder

– Five teenagers killed when their car gets hit by a train

– Federal government rules that US ships cannot haul alcohol

– A drunk driver is sentenced to jail

– a local rabbi is sued for divorce

– US ideas are spreading to China

– County post office is robbed

– Local man accused of embezzlement tries to commit suicide

– Local man denies killing his wife

– The city will be purchasing new snow plows

October 28, 1911:

– 19-year old found guilty of murder

– a plot was uncovered to smuggle dynamite from Indiana into Ohio

– war in China

– mayor is accused of corruption

– John D. Rockefeller is sued for illegal business tactics

– Body of a drowned man is discovered

– labor leader is accused of murder

– A pastor is accused of murder

– Local man is accused of abducting a teenager girl

– President Taft, it is reported, has failed to register to vote in his home town

October 29, 1947:

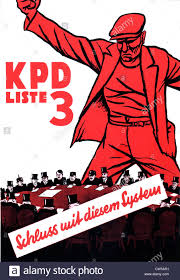

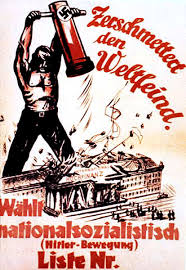

…and this one’s from 1948 instead of 1947, but we still worried that communism was going to destroy the world.

– Mayor is accused of firing policemen because they belong to the opposing party

– National hysteria over communism may threaten civil rights

– Men in two small planes are trying to circle the globe

– riots in Paris seem to be provoked by communists

– Free trade agreement signed by US and Britain

– property values and taxes are increasing

– local bus drivers in contract dispute

– Communist officials in election in Denmark lose some support

– Fund-raising is taking place for local community chest

Overall, most of these news stories will not make one feel all warm and happy and peaceful inside. Maybe the new snowplows, if you are into that sort of thing.

The point, of course is that if you regularly read the newspaper from any time in the past century, it could also make one think, “Man, the world sure is a mess.” The years above are not even known as particularly tragic years in the 20th century.

Of course, there really is something wrong with the world. These are real stories.

But the news is a funny thing. It tends to dwell on conflicts, tragedies and evils of the world.

And it does not tend to report other kinds of things. For instance, imagine some kinds of things the news did not report, in 1922, 1911, 1947 or 2016:

– Yesterday a father in Nashville, Tennessee went out to his backyard and played some ball with his two kids. They felt loved.

– Neighbors in a village in China yesterday talked with an elderly woman whose husband just died. She was comforted.

– Nobody in Canada rioted, attempted to take over the military, or shoot a politician yesterday when election results showed the ruling party had lost. The country moved on in a peaceful transfer of power.

– A small church in Los Angeles reports that a dozen couples in the past year have grown stronger in their marriage and, despite instances of difficulties, have become more dedicated than ever to one another.

If you worked at it, you could imagine hundreds of similar events that take place in our society and in the world that don’t count as “news.”

But why does our news function the way it does? More on that later.