Do you remember that riot in Philadelphia, the “City of Brotherly Love?”

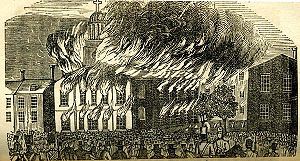

The one that lasted for three days, where crowds burned more than thirty buildings to the ground, including two churches? And four people died?

It was the one where the poor people in the urban areas felt they were being systematically discriminated against. So they rioted.

Over the Bible.

Yep, I’m talking about that event in American history that we all learned about in high school history class: The 1844 Philadelphia Bible Riots.

As my students might ask, “That was a thing?”

Yes. The Philadelphia Bible Riots were a “thing.”

(The riots are also known as the “Nativist Riots of 1844” but some people called them “The Philadelphia Bible Riots.” That’s the term I prefer, because that’s just the kind of guy I am.)

The situation? The Philadelphia school board had passed a policy allowing Catholic students in public schools to take their religious instruction from Catholic leaders. In response a mob marched into a Irish neighborhood and approached a fire station operated primarily by Irish Catholics. Somebody fired a shot and the riot was on.

So, you see, I was not giving you the whole story. They did not really riot over the Bible. They really rioted over a school board policy.

As if that makes more sense.

Why burn down thirty buildings over a school board policy? How can a committee meeting lead to four deaths?

Yes, we still do not have the whole story.

Here, then is my main point about riots: there is always a backstory. We may read about an event that sparks a riot, but the spark is not the cause of the riot. The causes lie in patterns, systems and actions that have been in place for years beforehand. That’s the backstory.

Let me briefly explain the backstory to the Philadelphia Bible Riots. (The whole story is more complicated, but this is a blog post, so you get a summary. For a fee, or a good hamburger, I’ll give you more than a summary).

The backstory to the Philadelphia Bible Riots is that Irish immigrants, escaping poverty in Ireland, had been pouring into eastern cities for about a decade. They were poor. They were also more likely to commit crimes, fall into domestic abuse and abuse alcohol than the wider population. And they faced prejudice and systematic discrimination.

You may have heard the old phrase, “No Irish Need Apply.” This was that era. Because many native-born Americans viewed the Irish as dirty, disruptive, violent, drunkards, the Irish often had a hard time getting decent jobs. Like many immigrants down through history, they took the jobs that other Americans did not want: digging canals, building sewers, cleaning streets and hauling manure.

For most non-Irish Americans, it was just fine that the Irish took these undesirable jobs. But what if the Irish immigrants started to work their way into higher level jobs? And what if they agreed to take these better jobs for less pay?

In fact, that is exactly the Iris immigrants would do. Employers knew this. Employers also knew a good thing when they saw it. If they could hire two dozen Irish immigrants for semi-skilled work for less pay than the non-Irish, they’d fire two dozen semi-skilled non-Irish workers and hire the Irish. As a result, job competition led a lot of working class non-Irish Americans to resent the influx of Irish immigrants.

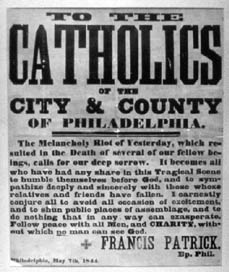

Then — as now — community leaders called for a peaceful approach to the conflict. This broadside came from Catholic bishop, Francis Patrick.

Remember also that this was an era before unemployment compensation, food stamps, insurance or pensions. There were no safety nets. So if you did not have a job, you faced starvation. The stakes were high. Many would be willing to turn to violence against those who threatened job opportunities.

But there is more. The Irish were also Catholic. Many Protestants at this time (who dominated the nation, numerically and culturally) thought of the U.S. as a Christian nation. But in their minds a Christian nation meant a Protestant nation. Catholicism was seen as anti-democratic and a barrier to progress. Many Protestants believed if a conflict arose between the pope and the Constitution, Catholics would blindly follow the pope. (Protestants never thought to ask what they themselves would do if a conflict ever arose between the Bible and the Constitution. Would they “blindly” follow the Bible?)

For their part, Irish immigrants were desperate to escape poverty in Ireland. Like your ancestors (if you are an American but are not completely Native American or African American) they came to the United States for opportunity. They were willing to take lower wages because that economic opportunity was better than what they had in Ireland. And most Irish were loyal Catholics. This meant they felt deeply the Protestant charge that they did not fit into America, despite its rhetoric of freedom. They held to the Catholic teaching that the Bible could only be properly interpreted by church authorities. Many were not happy to send their children to a school where the teachers would, in essence, teach a Protestant view of Christianity.

Neither the working-class non-Irish nor the Irish immigrants felt like those in power were really listening to their concerns. Working class non-Irish felt threatened by immigrant Irish, who felt threatened by working-class non-Irish. All believed their rights were threatened.

For just a glimpse of the passion and sense that immigration was a threat, check out this broadside from Protestant Philadelphians right before the riot broke out:

“The Americna Republicans of the city and county of Philadelphia, who are determined to support the NATIVE AMERICANS in the Constitutional Rights of peaceably assembling to express their opinions on any question of Public Policy and to Sustain them against the assaults of Aliens and Foreigners are requested to assemble on THIS AFTERNOON, May 6th, 1844, at 4 o’clock, at the corner of Master and Second streets, Kensington, and to take the necessary steps to prevent a repetition of it. Natives, be punctual and resolved to sustain your rights as Americans, firmly but moderately.”

Is it possible to riot “firmly but moderately?” Probably not.

So, you put all this together — cultural prejudices, intense job competition, perceived threats to American democracy, conflicts over the role of religion in the schools — and you have mixed together dry wood, oxygen and gasoline. That’s the backstory.

All it needed was a match. That was the school board decision.

This history can help us as we think about the riots of the past year. It is easy to focus in on the specific event — a police shooting — and think that this one incident is what caused the disturbances.

No. There have been hundreds of police shootings every year for years and they do not produce riots. An event like a police shooting is simply the match. The backstory is the wood, oxygen and gasoline piled up together.

The question for us, then, is this: how well do we understand the backstory of the recent riots?