(This is Part 4 in a series of blogs I am doing entitled “Why It Doesn’t Make Economic Sense to Run Education like a Business.”)

One day, when I was about eleven years old, I was in the Ford station wagon with my dad when the engine light went on. He stopped to pop the hood and we got out to peer at the workings underneath. “One thing to do when something is wrong is smell the engine,” he said. I looked at him, waiting for that important bit of advice that fathers pass on to sons. “I don’t really know what I’m supposed to be smelling,” he said with a chuckle, and we slammed the hood and got back into the car. This was the moment when it dawned on me that the entire automotive world was something of a mystery to my father.

My father, a Methodist minister, has many gifts. Automotive knowledge. I have several vacation memories of sitting on the side of the road, while we waited for the tow truck to haul away of one of the many station wagons we went through. A mechanic once informed my father that his Buick Skylark was actually two different cars — a 1980 body had been jerry-rigged onto a 1981 chassis by some mysterious party that had sold the vehicle to him. Our family still talks about the bright yellow Chevy Nova that blew out three different engines. And then there was our 1972 Chevy Vega. This car ran fantastically for years. Since this particular model has been called “The Worst Car Ever Made,” it is apparent to me that my father pretty much relied on dumb luck when he made his decisions to buy cars.

I don’t have more knowledge of cars than my dad, but I decided long ago to use a different method when purchasing a car. I have discovered research. I read Consumer Reports before I start to think about models. I have bookmarked Edmunds.com where I can determine the fair value of a car I am thinking about buying. And I always take a used car to be examined by my trustworthy mechanic before I buy it, since he has far more expertise I do. This research doesn’t guarantee that there won’t be surprises in the future, but it gives me a much greater sense that I know what I am getting into.

So we ought to be able to do this kind of research for a college education, right?

No. I don’t think it can be done.

Education is a different animal. Its unpredictability functions in a different way than car purchases.

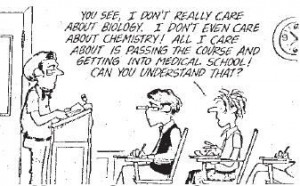

Even if we believe college education is about getting training for a job (a definition of education that is so narrow as to be impoverished, in my estimation), we can’t know for sure what we are getting into. For instance, many students are told, when they research potential colleges, they should choose a college with a good major in the field they want to study. On the face of it, this is solid advice as one sets out on a career, like looking for a car with good reliability ratings. But I have had conversations with countless numbers first-year college students over the years who aren’t really sure what they want to do.

Some say that if you don’t know what you are going to do for a career, you should take some time after high school graduation to do something else. This kind of “research” may be of great help…and it may not.

It would not have helped me. Like many young people at high school graduation, I did not know what I wanted to do, or what I would be well fitted for. The existence of hundreds and hundreds of possible career options did not help. What did I do? I had fooled around with one of the very earliest personal computers that our high school had obtained and thought it was cool, so I declared myself to be a computer science major when I entered college. I was unable to get into any computer science classes in the fall semester, but it took me about two weeks of a computer science class during my spring semester to realize that this was not for me. Programming, which is very different from fooling around on a computer, was not what I expected. Though I could do it, the work was a real struggle – I just did not “get it” as quickly as my classmates. And I did not find the work interesting, inspiring or fulfilling. I was not well fitted for it.

Meanwhile, I had taken a world history class during my first semester. I not only did well, but I enjoyed it greatly. And I had no thought that history was in my future until, late in the semester, my professor told me I had a knack for it. He asked if I ever considered becoming a history major. By the third week of my spring semester I had switched to history and it has proven to be a good fit. Indeed, I would say that God called me down this path.

…only to learn that you had really been driving this around for the previous six months? What kind of world is that? It’s college!

How could I have ever known that this is what I was getting into before that first tuition payment was sent in before fall semester? I only discovered this about myself by taking a computer science class and a college-level history class. Pre-college research would not have helped. In fact, that is the point. How can we know something before we learn it? A good college education is about education — which includes gaining a deeper understanding of who we are and how the world works. I can’t know what I am buying ahead of time in education, because education is about learning what I do not yet know.

And I’m just scratching the surface here. Even if you know what career you will pursue, how do you know how a particular college will affect your ethics, politics, religious faith, or relationships? How will a college education affect your understanding of science, culture, the arts, social institutions, gender, race, nationalism or thousands of other things?

It makes sense, of course, to choose a college with high academic standards. It makes even better sense (in my estimation) to choose a college that will direct your mind and your desires to what is good. Research can give you a rough idea of these qualities in a college.

But even this sort of research can be misleading. Just what do the U.S. News and World Report rankings tell us about the kind of education we will be getting? A recent Atlantic article argues, quite persuasively, that this ranking system is not what it claims to be.

And how about this: this very popular system of ranking colleges may be raising the cost of education. And, surprise, surprise, status (rather than educational outcomes) plays an outsized role in the ranking process – as I mentioned in an earlier post.

Consumer Reports gives me pretty good odds of how reliable my car will be. A college education, however, is a four-year process that involves the unpredictability of human growth, development, learning, and desires, all cast in a context with hundreds (thousands?) of others whose impact on us is unpredictable as well. We can learn much ahead of time about the type of college we might go to, but we can’t really know what the education will do to us.