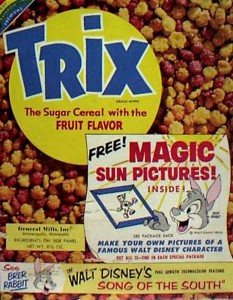

In 1954, General Mills introduced Trix cereal to the American public. This was the most significant event of the 20th century.

Really? More significant than the 1952 election? More significant than the 1929 stock market crash? More significant than Watergate?

OK, I’m overstating things here, but I’m actually pretty serious about this. The introduction of Trix cereal may rank in my top ten list of most significant events of the 20th century. Maybe the top five.

Why? Because Trix was the first multi-colored breakfast food.

Get it? Probably not.

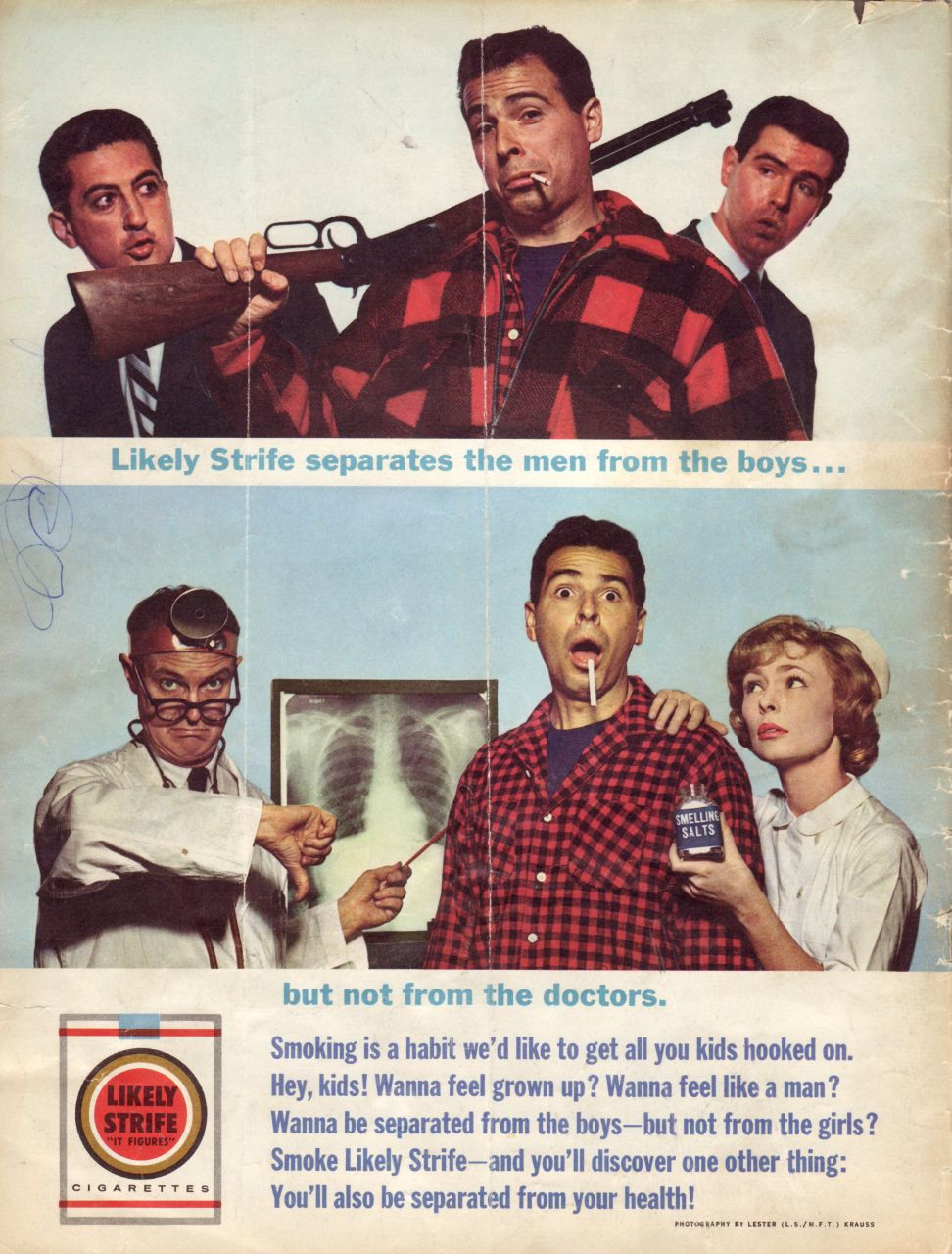

Think about why General Mills produced a multi-colored breakfast food and why they marketed it with that advertising campaign familiar to all Americans, “Silly Rabbit, Trix are for kids!”

Get it? Not quite, I’m betting.

Think about this: why did General Mills think that it would work to advertise to 4 year-olds during Saturday morning Bugs Bunny cartoons? Do 4 year-olds have the means to run out to the grocery store and buy Trix? Do 4 year-olds make the decisions about how the family income is spent?

Admit it. You want this.

Get it? I’m guessing we’re starting to get there. Remember what you were like at age 4 in the grocery store and you saw something you wanted? Or have you have observed 4 year-olds in grocery stores? It is a fascinating and rather unsettling sight. Watching 4 year-olds in the grocery aisle with their parents is like watching wildlife documentaries of elks fighting fellow elks for dominance. The fight may begin and end quickly, but in those short, dramatic moments, we glimpse a compelling struggle of power, will, wits and cunning, as we wait to see who will come out on top.

A little historical background to epic grocery store battles: In 1854 and 1754 and 1654 (and earlier, in just about everywhere around the world) children were producers in the family economy, but they were not major consumers. In other words, most children helped the family economy by working at tasks like herding livestock, sewing, gathering eggs, carrying water, etc. They did not make decisions about how household money would be spent. By 1954, that pattern was reversing in most middle-class families. Children produced very little to help the family income while becoming major players in deciding how the household income was spent. Even 4 year-olds. Amazing.

In other words, thanks to Trix cereal (and Barbie Dolls and Hot Wheels and Kool-aid and McDonald’s) all of us became consumers at a very young age.

Of course, I am using Trix cereal to represent a whole host of larger consumer trends at work. Targeting children in advertising began a number of decades before 1954. Plenty of other companies besides General Mills were joining in on this. Economic prosperity gave families plenty of disposable income. The growth of new forms of mass media – radio and TV, for instance – made it possible for marketers to reach children in their homes. But I use Trix cereal and 1954 as my representative example because the 1950s was the decade when all these forces came together in a powerful way in American society.

Sometimes, 4 year-olds choose Cinnamon Toast Crunch instead of Trix. Why? Because they can! They are consumers!

We have to ask an even more important question than the sheer economics of the thing: what kind of people do we become if we are shaped as consumers from the moment we can comprehend a TV ad? What does it mean to have a society in which consumerism holds formative influences on us as persons?

It means that we may enter into Christianity, marriage, civil life, education as consumers, rather than as disciples, spouses, citizens and students. As consumers, we are primarily interested in what we can get out of these things and are less likely to ask what we can contribute to them. It means we value things primarily on the basis of instant gratification and have little patience for self-sacrifice. It means that if we get dissatisfied, we may be quick to dump one option and go shopping for another. Does this happen? As that big red Kool-Aid pitcher used to say in the ads, “Oh, yeahhhhhh!”

A number of people have commented about how consumerism has affected American Christianity. Let me just point out one. Thomas Bergler has written an important book entitled The Juvenilization of American Christianity. One of the things he points out is that since the 1950s, evangelicals have effectively adapted the faith to the youth culture – a culture that is steeped in consumerism. As a result, evangelicals have been much more effective than other Christian bodies in attracting youth to church. The downside is that this sort of juvenile faith has spread through the adult levels of the church (think about all the ways that evangelicals want church to be “fun” and “exciting”). Christians with this kind of faith have a hard time moving beyond a rather shallow, self-centered faith based on immediate gratification. Why? Trix cereal.

A number of people have commented about how consumerism has affected American Christianity. Let me just point out one. Thomas Bergler has written an important book entitled The Juvenilization of American Christianity. One of the things he points out is that since the 1950s, evangelicals have effectively adapted the faith to the youth culture – a culture that is steeped in consumerism. As a result, evangelicals have been much more effective than other Christian bodies in attracting youth to church. The downside is that this sort of juvenile faith has spread through the adult levels of the church (think about all the ways that evangelicals want church to be “fun” and “exciting”). Christians with this kind of faith have a hard time moving beyond a rather shallow, self-centered faith based on immediate gratification. Why? Trix cereal.

Do we tend to view marriage relationships in terms of what we can get out of it? Are we, as a society, too willing to dump a spouse if we see a better product come along? I have heard evangelicals blame a number of things for the rising divorce rates of the last half century: the absence of prayer in schools, homosexuality, and something as vague as a “decline in morals,” just to name a few. We’re looking in the wrong places. We should start by thinking about our Trix cereal ads.

Civil society? In 1960 John F. Kennedy said, famously, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” It was a view of civil society that resonated with many Americans at that time. In the 2000 presidential debate, an audience member asked the candidates, “How will your tax proposals affect me as a middle-class, 34-year-old single person with no dependents?” Think about this one. It implies that as a voter I will make a choice based on a specific policy is tailored to a very narrow slice of the population who are just like me. And did Americans in 2000 even notice that this is a very consumeristic approach to viewing civil life? No, because this is an idea of civil society that resonated with many Americans, who all grew up enmeshed in consumerism. “Silly President, tax policies are for 34-year old single persons with no dependents!”

Education? Don’t even get me started. I could describe how some students expect course offerings, class projects, and course expectations to conform to their personal schedules. I hardly need to tell you that many students believe classes ought to entertain them. Colleges feel compelled to offer a consumer lifestyle – good food, climbing walls, fun activities, stylish dormitories, exciting athletic programs – in order to attract students to come to their institution to get an education. My daughter once received a postcard from a college whose entire message was that they were “#1 in Food and Fun” in Ohio. The postcard said absolutely nothing about education. But food and fun? Ah, yes, that is what college is all about, isn’t it, Silly Rabbit?

Trix cereal: the most significant development of the 20th century.