I have a quiz for you.

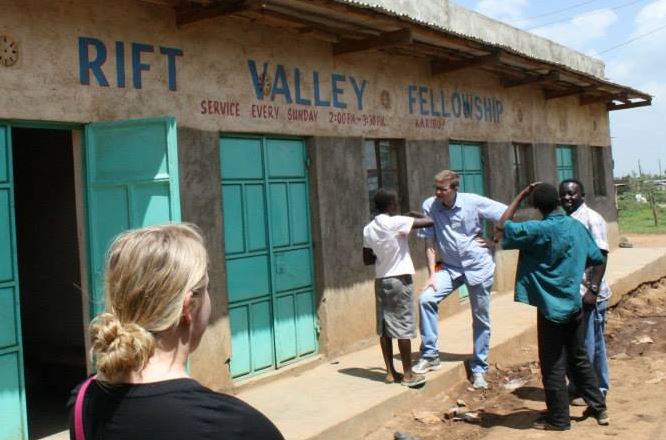

It’s the same quiz that I gave to my students toward the end of our trip in Kenya.

I told them that I had observed another group of evangelical Americans in a short-term mission situation where they were speaking to very poor people, most of whom did not have jobs and some of whom were homeless. I told them about a mini-sermon one of the Americans had given and asked them what made this sermon less effective than it could have been. Here is how it went: one of the Americans got up with an old bicycle. He explained that when you get on a bike, you choose where you go. You decide what path to take. You decide if you are going to go to work, or to school, or to a friend’s house. And that is how it is in life, he explained. We make choices about how we are going to live. We decide what job we are going to take and what we are going to do with our life….

At this point, several of my students groaned and several others rolled their eyes.

They passed the quiz. How did you do?

My students groaned because (as they explained to me) the poor women and homeless street boys in places like Maai Mahiu simply don’t have the choices that Americans have. They can’t choose what job to take, for instance, because in a poor town in a nation with about 40% unemployment and another 30% underemployment, jobs are desperately hard to find. Yes, poor Kenyans do have choices – moral and spiritual choices, especially — but their choices in so many areas of life are extremely limited.

Would you tell people from the slums of Kibera that they can “be anything they want to be, if they just work hard enough?”

My students were right. These Kenyans don’t believe that they “can be anything they want to be, if they just work hard enough” (another phrase I heard from an American in that group). These Kenyans know that this phrase is simply false. And so, there was a real disconnect between this American way of thinking and the reality of life for these people.

I then asked my students why they knew this and this other team from America did not. My students had to reflect on this for a few moments. Someone finally concluded that they listened to the people they met at Maai Mahiu. My students knew that they should try to understand the situation that these people were in.

But why did these students listen? Why did they know that they should work to understand the people of Maai Mahiu? I told them to think about their education. Excluding the specific class they were taking for this trip to Kenya, where had they learned to listen and understand people who were different from them? They then discussed a range of classes that they had taken at Malone where they did these sorts of things. Seven different classes were named specifically.

Why does this matter? It matters because far too many American evangelicals embark on short term missions trip without a deep sense that, even though they may go to serve, they also need to be learners. They need to be ready and willing to deepen their understanding of the people they serve. Far too many evangelicals take the attitude that since they have Christ in their lives, they do not need to learn anything about the people they visit. They just need to “love on” others and everything will be fine.

But it is not fine. It is true that God’s grace still works, despite our faults. It is true that love conquers a multitude of sins. It is true that this group that I used as an example did some wonderful things. But it is also true that our efforts can be limited or distorted because of our sins. It is true that the sin of pride, in assuming we know all we need to know, is a sin that we don’t have to commit. Many cross-cultural sins can be taken care of through a servant attitude toward learning. But without a humble attitude toward learning, well-intentioned short-term missions end up with limited effectiveness. I talked with several Kenyan Christian leaders who, while welcoming and supportive of Americans coming to participate in their ministries, indicated that some groups do not have a good sense of these things. As my friend Esther said, (in a phrase I find simultaneously telling and painful), she has seen many Americans arrive in Kenya with an attitude that “the Savior has landed!”

These American evangelicals probably would be surprised to find a good number of African Christians whose spiritual maturity is much deeper than their own.

Of course, there are American evangelical leaders who understand these things. For instance, I know of a famous Baptist preacher who said, in a speech in a missions convention, that we must carry out “our ideas as being ourselves learners.”

But wait. That Baptist guy was Francis Wayland who was born in 1796. He gave the speech in 1854.

1854!

I mention this because as a historian of these kinds of things, I can find evangelical missionaries saying roughly the same thing to their American audiences in about every decade since the 1850s. Many evangelicals don’t get it. They don’t listen. And they don’t learn. The result? We keep on sending people out into cross-cultural situations who do not draw upon the insights from the past. As a result, every generation has to reinvent the wheel. It is still happening today, folks.

Here is one small suggestion: if you belong to a church that sends out short-term missions, see what you can do to help your church prepare for these trips. I would recommend a book by David Livermore called Serving with Eyes Wide Open: Doing Short-term Missions with Cultural Intelligence. It is very thoughtful, accessible, and written with ordinary evangelicals in mind.

If your church group reads this book and takes it seriously, they will go out with greater cultural intelligence. They are less likely to give off the impression that, now that they have arrived, the Savior has landed.

(And for those of you who are weak on your theology, let me mention that the Savior landed about, oh, two thousand years ago).