If you want to better understand how all of us came to hold the conviction that slavery is wrong, you might consider the following claim:

“The abolition of New World slavery depended on large measure on a major transformation in moral perception—on the emergence of writers, speakers, and reformers, beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, who were willing to condemn an institution that had been sanctioned for thousands of years and who also strove endlessly to make human society something more than an endless contest of greed and power.

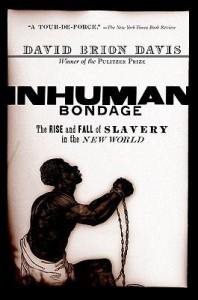

David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage, p. 1.

That is quite a claim, when one thinks about it. How often do unjust institutions get struck down, particularly if those institutions have existed for all of human history and could be found in every region of the world?

I am a historian, so I will give you an authoritative answer: not often.

For many reasons, then, I think we would all benefit from greater understanding of this historical development. And so, as a little post-game wrap up to my contest between James Bond and Samuel Sharpe, I’d like to recommend a book. Like millions of others, you can entertain yourself by watching the new James Bond movie, which is fine, but you should also consider the riches of a historical work that deepens your understanding of the world and how it works.

The book, by David Brion Davis, is Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. After a career of extensive and thoughtful study of slavery, Davis wrote this book to explain how slavery came to dominate the Americas and then how it was eventually abolished. The story is complicated, but Davis condenses a mountain of historical scholarship into a quite readable form, which is one of the reasons that it won the Pulitzer Prize.

Part of the reason why I find this story compelling is because I believe that the hand of God was behind the abolition of slavery. Davis does not mention the hand of God in the book. I do not know what Davis’ religious convictions are and I am guessing that he would not agree with my claim that I can see God at work. As a rule, academic historians do not try to determine if God is at work in history. Academic historians do give careful consideration to the human forces that lead to historical change and Davis, who is an excellent historian, does that quite well.

Part of the reason why I find this story compelling is because I believe that the hand of God was behind the abolition of slavery. Davis does not mention the hand of God in the book. I do not know what Davis’ religious convictions are and I am guessing that he would not agree with my claim that I can see God at work. As a rule, academic historians do not try to determine if God is at work in history. Academic historians do give careful consideration to the human forces that lead to historical change and Davis, who is an excellent historian, does that quite well.

I plan to discuss more of this later. For now, I would think you might find it interesting to read this book with a couple of questions in mind: was God at work in this movement? And if so, how?

Oh, and if you are ever in Jamaica, ask your van driver to tell you about Samuel Sharpe. I am sure that he or she would be very pleased to tell you about him.

1) Historians are useful people. 2) Damn you, Case. I don’t have time to read this book, but now I have to.

Pingback: Understanding Your Ethical Conviction that Slavery is Wrong

If the “hand of God” is at work in abolition, it’s certainly strange that abolition never found it’s way into biblical inspiration. And strange that it took God thousands of years of human history to show his hand.

That’s an interesting idea and one that rightfully deserves far more discussion than can be given in this format. But here, briefly, are a few additional ideas to consider: it is not actually self-evident that abolition never found it’s way into biblical inspiration. While many Christians, especially in the 19th century, would have read and interpreted the Bible the way you do, other Christians found the principles for abolition in the Bible. Most Christian slaves, for instance, believed the Bible said that God worked for liberation. Thus, one could argue that God was at work, but humanity, in a sort of self-serving stubbornness for which it is often guilty, failed to understand the point.

But if we assume that God was not involved in abolition, for whatever reason, we still have a similar intellectual problem in understanding this historical development. Why did it take humankind thousands of years of human history to figure this out? Why did humanity turn to abolition in the 19th century and not at some other point in history? Did humanity get smarter? Did humanity become more moral? If so, why, and how did that happen? Those aren’t easy questions to answer, from any perspective. To me it seems that one has the same sort of problem of causality if God is not in the picture.

I would recommend the book “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined” by Steven Pinker, a professor of psychology at Harvard. Pinker argues that, in spite of modern terrorism and the horrors of twentieth century dictators, in terms of percentages of humans subjected to violence by humans, humanity has grown steadily less violent throughout history.

I don’t see a “problem of causality” when living cooperatively and altruistically clearly has selective advantages for humans.

As for the Bible, I suppose one could take general passages about love and how one treats neighbors and apply them to slaves; but it’s far easier for the slave owner to point to OT passages clearly commanding enslavement of other tribes and NT passages commanding slaves to obey their masters.

So to the question, did humanity become more moral, the answer is a resounding “yes!” More moral than the Bible.

A harder question to answer would be: did we become smarter or more moral individually. I wonder if, instead, we’ve gradually built societal norms that are smarter and more moral. New scientists don’t have to figure out Newtonian physics because Newton already did that work and left it in writing. Perhaps our babies are born no less moral than babies born 2000 years ago, but the moral values babies learn from parents has improved steadily over time.

Thanks for your book recommendation, but I had already purchased Pinker’s book several months ago. I do hope that he is correct that the world is getting less violent. And I have to say that he marshal’s an incredible amount of sources to defend his argument.

I disagree with several of his assumptions, but that is a topic for a different forum. The main problem I have for our purposes here is that he tends to refer to historical evidence that supports his own interpretation, while ignoring or misrepresenting evidence that does not support it.

For instance, with regards to abolition, he declares that the Enlightenment brought this violent institution to an end, largely because abolition occurred at roughly the same time as the Enlightenment. But correlation is not causation.

What Pinker misses is that Enlightenment thinkers did not lead the way in abolition. Many of them grounded their thinking about other societies in deeply racist assumptions about nonwhites — as were most social scientists through the 19th century — which was not a recipe for abolition. You might want to check out what David Brion Davis has to say about Voltaire, Kant, Hume and Jefferson on p. 74-75 of “Inhuman Bondage.” Meanwhile, Pinker is careful to point out that Christians were racist, without mentioning Christian activity other than passing references to Quakers. Pinker says that many Enlightenment thinkers opposed slavery and then were “joined by Quakers.” The reality is that Quakers (who were promoting egalitarianism before John Locke published “Two Treatises on Government”) were the first to actively promote antislavery and were quickly joined by evangelicals — both of which borrowed some ideas from the Enlightenment, but were largely driven by their religious faith. These two Christian movements, arguably, formed the backbone of the abolitionist movement. Those Enlightenment thinkers like Ben Franklin who came around to antislavery positions, joined movements that had already been started by Christians.

You say that you suppose that one could take passages about love and how to treat one’s neighbor from the Bible and apply it to slavery. That is a good start. But one doesn’t have to end just by supposing. One can carefully examine the historical evidence of the primary leaders of the abolition movement. When you do, you will find evidence, in fact, that they did find in the Bible the inspiration, principles and motivation for their abolitionist efforts.

And that goes back to my earlier point in the previous reply: just because you read the Bible one way, doesn’t mean everyone else reads it the same way. What is “clear” to one person is not “clear” to another. (Compare Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Campbell, for instance, who both believed that the truth of the Bible was perspicacious, but ended up with very different conclusions about what it said). That is why it is possible for Christian slaves and abolitionists to be inspired by the Bible – along with new ideas about equality–in their efforts to eliminate slavery, while slaveowners could marshal proslavery arguments from the Bible (though these arguments were never as forceful as secular proslavery arguments). Meanwhile, Kant and Voltaire and Locke, utilizing different texts, were certainly not out on the front lines on abolition.

I absolutely agree you that social norms were created that we have inherited. That, in fact is the very point I made in my previous post on November 24. Pinker interprets the establishment of these social norms according to his faith in the assumptions and evidence of evolutionary psychology. I interpret the establishment of these norms according to my faith in the assumptions and evidence about how the Kingdom of God unfolds. And so we disagree.

The truth is that both religious and enlightenment figures were on both sides of the slavery issue, and the attempt to set them up as competing forces is bogged down by the fact that most enlightenment figures were Christians.

Pinker does not, as you assert, assume an enlightenment influence on abolition simply through “correlation”; he’s more specific than that. And he credits Quakers for their contributions. Outside of the abolition discussion, Pinker even credits Jesus for principles of nonviolence. He does make the point, of course, that Christianity, as a worldwide religious movement with enormous influence on governments, failed to reject slavery for 1500 years.

While you are free to interpret history through faith and evidence, I don’t think Pinker would concede that faith is a part of his assessments.

Well, at any rate, I am eager to read the David Brion Davis book.

Yes, you are correct that religious and enlightenment figures were on both sides of the slavery/abolition issue. I may have overstated my point a bit by implying they were competing sources, which I should not have done.

The problem, as i see it, is that Pinker does not get the role of religious faith correct in his analysis of abolition, portraying it more as a handmaiden to larger, more important Enlightenment and Age of Reason forces. And I don’t think the evidence supports that analysis.

Pingback: That Was The Week That Was « The Pietist Schoolman

Pingback: That Was The Week That Was « The Pietist Schoolman

Pingback: edu backlink service

Pingback: led tv

Pingback: Weston Vanscoter

Pingback: Sebastian Astolfi

Pingback: Vena Coaster

Pingback: Tristan Mannix

Pingback: Ashli Gonzelez

Pingback: Marcelino Kaczor

Pingback: Calvin Corsetti

Pingback: Scarlett Banasiak

Pingback: Owen Mormon

Pingback: Ward Woolverton

Pingback: Sol Stephen

Pingback: Manuel Karstetter

Pingback: Norman Linnear

Pingback: Hui Sabini

Pingback: Marchelle Lawnicki

Pingback: Lemuel Caston

Pingback: Gayle Altew

Pingback: Joan Spearing

Pingback: Kellee Feagins

Pingback: Kiera Eichholz

Pingback: Maryln Causby

Pingback: Emmanuel Gallosa

Pingback: Ka Alzaga

Pingback: Williemae Jumalon

Pingback: Miesha Capener

Pingback: Clifford Clothier

Pingback: Dennis Durough

Pingback: Bradly Wilhelmsen

Pingback: Wally Leyson

Pingback: Tobias Leite

Pingback: Julio Berentson

Pingback: Tobias Leite

Pingback: Stanford Couchenour

Pingback: Hazel Lazaga

Pingback: Roy Henehan

Pingback: Darin Guitierrez

Pingback: Alphonse Draggett

Pingback: Randolph Strande

Pingback: Leisha Peters

Pingback: Shoshana Werbelow

Pingback: Vida Jaksic

Pingback: Minh Buhrman