James Bond or Samuel Sharpe: which one should we be most interested in? Today begins our head to head competition between the two (see the previous post for details). Round one begins with the topic of redemption and violence.

James Bond is in the redemption business. He tries to save the world from bad guys and bad women who come in all kinds of different sizes, shapes and nationalities. And he saves the world, every time of course, usually by killing the bad guys. At one point in “Dr. No,” the first Bond movie (filmed in Jamaica), Bond knifes a guy from behind who was trying to track him down. “Why did you kill him?” asks Honey Ryder. “I had to,” replies Bond, coolly. According to the logic of the film, the world won’t be saved unless Bond kills bad people. We see him kill five individuals at different points in this film, not including those who might have died when he blows up Dr. No’s secret nuclear powered radio beam laboratory at Crab Key in Jamaica.

But is it interesting? Well, yes, on one level. Several Bond films have hit the top 100 grossing films of all time. A lot of people are quite interested in stories in which a hero or set of heroes kills off bad people who threaten to destroy society. It is one of the most common stories humankind tells itself. And it is very common in film. (Just think Star Wars, Spider Man, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Rambo, the Avengers, Little Mermaid, your typical western, your typical war movie, any film with Arnold Schwarzenegger in it where he does not get pregnant, etc. etc. etc.)

Now, I have to confess that, personally, I don’t find this basic formula extremely interesting, partly because it is so very common. I am, however, extremely interested in why so many people find this kind of story interesting, but that’s a question for another day.

So what about Samuel Sharpe?

Sharpe was also in the redemption business. He was a Baptist evangelist, which meant that he was interested in the salvation of souls. But he also was very interested in saving society from the oppression of slavery. As a result, he attacked that system. But his story unfolded much differently than the typical Bond film. Let me highlight two points.

First, if the goal of a rebellion is to kill the bad guys, the Jamaican slaves proved to be stunningly and amazingly ineffective. Sixty thousand slaves rose up, fought for one month and in the process killed…..fourteen whites. 60,000 to 14. Has there ever been a smaller proportional harvest of dead bad guys than that? James Bond could knock off that many bad guys in about three minutes of hand-to-hand fighting in an ordinary atomic laboratory.

What kind of rebellion was this, anyway?

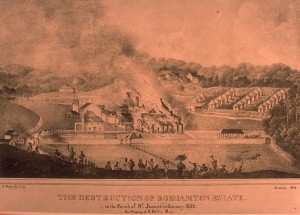

The Baptist War was a rebellion that intentionally targeted property rather than people. The slaves burned hundreds of houses and attacked sugar mills. Sharpe explicitly told the rebels that they were to drive the slaveowners off the estates but they should not harm them, except in self-defense. What a strange strategy. More strange was that 60,000 slaves should listen to it. Burdened by a terribly oppressive system and given the opportunity to vent their frustrations, why should they exhibit this amount of self-restraint?

The slave rebellion was crushed. In the end, 500 slaves were killed or executed. The rebellion was a failure. Slavery was not abolished in Jamaica.

But the story does not end there.

Slavery was not abolished, that is, until one year later, when the British Parliament emancipated the slaves in all its colonies (except those under the control of the British East India Company). And here we come to the second very interesting part of this story. The self-restraint and relative absence of violence on the part of the slaves played a key role in abolition. In a round-about way, the slaves won, even after they lost the rebellion.

It’s a long and complicated story, but here are the relevant points for our purposes: abolitionists in Parliament had been working for decades against formidable opposition. They had managed to ban the slave trade and slavery in Britain. It was tougher going to ban slavery in the colonies.

By 1831, political conditions made it look like abolition was in reach. The key lay in persuading enough politicians and their constituents to put the vote over the top.

But most Brits had the 1791 Haitian slave revolt in the back of their minds. That revolt left 10,000 blacks and 2000 whites dead. It provoked an even more violent twelve-year rebellion. As a result, the Haitian revolt left an ambiguous legacy. It proved that abolition was possible. But the violence of the rebellion terrified whites in Europe and the Americas. Stores of atrocious acts of violence by blacks (though not those of whites against blacks) circulated among white populations for years afterward. The revolt reinforced racial stereotypes of blacks as savage beasts and encouraged many whites to believe that emancipation would lead economic ruin and the wholesale slaughter of whites.

Had the Jamaican slaves in 1831, then, set out to kill as many slaveowners as possible, they most likely would have turned a great chunk of British public opinion against them. Samuel Sharpe, who had received news from missionaries about Parliamentary negotiations, knew this. Thus, the orders for self-restraint.

And it shaped the political discussion in the months after the Baptist War. Instead of hearing speeches denouncing savage brutality of blacks who wanted to rape white women and massacre the English, MPs in London heard missionaries testify about the cruelty of the planters and the execution of Christians like Sharpe. Black slaves no longer looked like savage beasts. It became more possible to conceive of them as free citizens. Although there was more to the story, the relative lack of violence by the Jamaican slaves played a key role in their redemption from slavery. How strange.

And what an interesting story of violence and redemption.

Score: James Bond 0

Samuel Sharpe 1

Thanks, Jay! You are helping us revise our histories of violence as liberation,