I learn things from my students. I don’t tell them, because then they’ll want to grade me on it.

One thing I learned from them is that there is a democratic characteristic that Americans do well. I learned this through an anecdote I gave in class. Yes, this post is an anecdote about an anecdote.

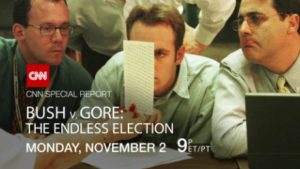

One day, several years ago, I brought up the 2000 presidential election in class. I explained how it was essentially tied between George W. Bush and Al Gore after election night. Florida, which was still too close to call, would decide the election, based on which way it went. They had to count and recount the votes, and then get rulings on which votes were valid or not and why. I explained that this went on for weeks.

The United States faced a major electoral conflict.

I then fast-forwarded my anecdote. I explained to my students that about a year later I was talking to a guy who had been a missionary in Macedonia during this election. He was talking to some Macedonians during the weeks when the results in Florida were disputed. These Macedonians explained that the solution to this problem was really quite easy. Look, they reasoned, it is clear that most Americans want Gore to be president because he got more popular votes than Bush. (As you know, we have this funky electoral college system where every now and then the candidate who won the most popular votes did not win the election. Even though Gore had more popular votes than Bush, the winner of Florida would gain the majority of electoral votes to win the presidency.) Gore was Vice-President, which means he had President Clinton’s support and authority over the military. So here, according to these Macedonians, is how to solve the problem:

Gore should just take over the military, roll into Washington DC with the tanks, and declare that he is the rightful president.

At this point in my anecdote, a couple of students laughed. They guffawed.

Now, my intention in telling this story was to get my students to think, “Hmm, this is interesting. These Macedonians sure think about government and elections differently than us.” (It’s a quixotic and perennially idealistic hope I have as an educator: that students would think that something, anything, I bring up for discussion is interesting.)

I realized upon reflection after class, however, that these students did not think the Macedonian solution was interesting, so much as it was absurd.

The semester after that, I told the same anecdote. And the semester after that and after that. I always got similar reactions. A few students would guffaw. Those who commented on the anecdote viewed the Macedonians with some incredulity, as if they were absurd.

After several semesters of reflecting on this sort of thing, something else occurred to me:

My students’ reaction to my anecdote was a very good thing.

My students know, in their bones, that it would be absurd to think Al Gore should or would use the military to solve an electoral crisis like this. And actually, this idea is absurd to Americans (and Brits and Germans and Belgians and Japanese and some others). We are convinced that this is an inappropriate and even dangerous use of the military. It is, in fact, a serious threat to democracy. Our reaction of incredulity shows we do this well, without realizing it.

But this is what is interesting (and not absurd): The idea that you should turn to the military to “solve” a political crisis is not absurd to many people around the world.

In fact, if I could bring a bit of basic Christian theology into this, I would argue that the default tendency of human beings, because of our sinful nature, is to think we are justified in using the military to solve deep political problems. Because, of course, all the evils of society lie with our political opponents. They are the threat to what is good and right. They deserve to be forced to come to the truth. Grab the guns.

It is actually rather strange and uncommon to think these things should be worked out peacefully. Authoritarian systems, however, foster the belief that the military can “solve” political crises. This is why it is not surprising these Macedonians thought this way. They did not have a history of democracy. For the last half of the twentieth century, they lived under the communist government of Yugoslavia. Before that, it was a Yugoslav dictatorship. Before that, it was the Austrian Empire. Before that, it was the Ottoman Empire.

Separating military force from politics is a very difficult task for democracies to achieve. I could point to hundreds of historical examples. (I am not exaggerating that number.) Take, for instance, the French Revolution, which attempted to overthrow monarchy and give power to the people in 1789. A noble goal, but things got….messy. (Can you say “Reign of Terror” boys and girls? I thought you could.) After several years of political disorder, Napoleon, at the head of the military, staged a coup and took dictatorial control of the nation, later crowning himself Emperor. So much for democracy. But most of the French loved him for it.

Dating back to the 19th century, Latin America has had a long tradition of turning to a figure called the caudillo. The caudillo was a popular military leader who takes over by force when there is disorder or conflict in the nation. He was often a charismatic figure, supported by masses of people who want somebody to bring order. He did not bring democracy — in fact, he often used force to restrict liberties, but his supporters were fine with this. This is a cultural tradition that democratically-minded people in Latin America would like to bury.

In any given year, one or two of the four dozen nations in Africa will experience a coup or an attempted coup. In Asia, Thailand has had two coups in the last decade. In July of this year, the military in Turkey attempted a coup and failed. The Turkish prime minister, Erdogan, has used that event to stomp on a whole host of democratic freedoms and arrest political opponents. Coups, regardless of whether or not they succeed, are not good for democracy.

In 2000, the U.S. solved its electoral crisis in the courts. It took several weeks. It was messy. Some people were embarrassed or critical of the process. And certainly, the electoral process had its problems.

At its core, however, the 2000 electoral conflict was actually an example of a great strength of democracy (and would have been equally so if the courts had ruled in Gore’s favor). The United States did not turn to the military to solve its political dispute. Given human nature and the examples of history, this is not something to brush off as trivial.

Many Democrats thought the result was wrong and unjust. They sincerely believed that Gore should have been ruled to be President. But Al Gore and the Democrats did not even entertain the idea that he should grab the guns to make right what they thought was wrong. It wouldn’t have worked anyway, because Gore would not have had the support of the American people, the military, or even those in his own Democratic party. The same would have been true if it were the other way around and the ruling had gone against George W. Bush and the Republicans.

Americans do this well. As do other solid, stable democracies. Without realizing it.

So, as long as my students continue to guffaw at my anecdote, I will feel very good about this part of the American political culture.